An apologia for custom work

Nancy Hiller has done her best to ensure that custom work is a source of satisfaction, as well as a source of income. Here are a few of her tips.

Several years ago I was talking with a fellow woodworker about a kitchen I’d designed and was eagerly looking forward to building. After poring over the drawings, he said he loved the design; then, referring to his own business, he said wistfully, “Custom work is Nowheresville.”

I was taken aback. After all, as with all of the kitchens I design and build, this one clearly qualified as custom work. It turned out that my friend was referring to the kinds of jobs people ask you to do when you first hang out your professional-woodworker shingle, a gesture Josephine Public tends to interpret as “I’m a woodworker. Bring me your requests to build closets with cheap plywood bypass doors…your orders for aquamarine-epoxy river tables…your queries about what it will cost to repair that set of poorly made chairs you bought at a yard sale” (all for a fraction of what your labor and operating expenses demand you should charge).

It doesn’t have to be this way.

I have made my living largely as a designer-builder of custom furniture and cabinetry for most of my adult life. The first several years I worked for others; since 1995 I’ve worked in my own business. While it’s been anything but easy for many of those years—and especially during recessions—I’ve done my best to ensure that custom work is a source of satisfaction for me, as well as a source of income. Here are a few of my tips.

Take charge of your identity

When I first established my business I made clear in every bit of promotional material (business cards, local public and community radio underwriting, what advertisements I could afford in my local market) that I did custom work: I design and build to suit my clients’ desires and budgets. I organized my business this way because I lacked the kind of financial backing that might otherwise have allowed me to build a portfolio of pieces to my preferred aesthetic, then market them (and store those that didn’t sell…). My reason for stating that I did custom work was not to invoke a buzzword (“custom,” like “bespoke,” is too often dangled before potential buyers’ eyes as the tradesperson’s equivalent of a rap star’s “ice,” intended to imply a certain high-dollar cachet); it was simply honest. But just as important in business terms, it widened my net for getting potential jobs. For many years I lived alone, with no second income to help with business and personal expenses. It was imperative that I stay busy with paying work.

But just because you identify yourself as a custom furniture maker doesn’t mean you can’t qualify that title to inform others of the kind of work you prefer to do. Whenever possible, I add something along the lines of “Specializing in work for homes and offices from the late-19th through mid-20th centuries.” This helps potential customers find me, whether they see my yard sign in front of a house where I’m working or are pointed in my direction by a friend who’s heard an underwriting announcement on WFHB.

Work to find satisfaction in whatever commissions you get

Sure, I prefer to design and build work that’s at home in old houses, but I know myself well enough to acknowledge that if I had the luxury to work only on designs I love, I’d be in danger of going insane. I need variety. This makes custom work ideal for me. Besides the period-style work I’m known for, I’ve made a custom laundry cart with orange wheels, a sink base to match the original 1940s amber plywood cabinets in a mid-century kitchen, and custom wooden urns for three clients’ loved ones’ ashes. My most recent commission is a two-person bench that riffs on a pair of lipstick-red, factory-made CB2 chairs. And this list represents the mere tip of the iceberg. Each one of these arguably oddball commissions has stretched me with aesthetic and technical challenges; I’m always learning. I like that.

Learn to value collaborating with customers

Working to commission keeps me honest. There’s nothing like taking a commission to build a 5′ x 5′ dining table to match something a client found online but wasn’t available at those dimensions to keep a check on the ego and restore humility. Making solid-wood furniture that looks as flawless and slick as that made from MDF in a production factory entails all sorts of challenges. While it’s not something I want to do more than (very!) occasionally, I do want to help clients get the furniture they’re hoping for. If they’re nice people who are happy to pay my charges and wait for a turn in my schedule, I’m generally happy to oblige.

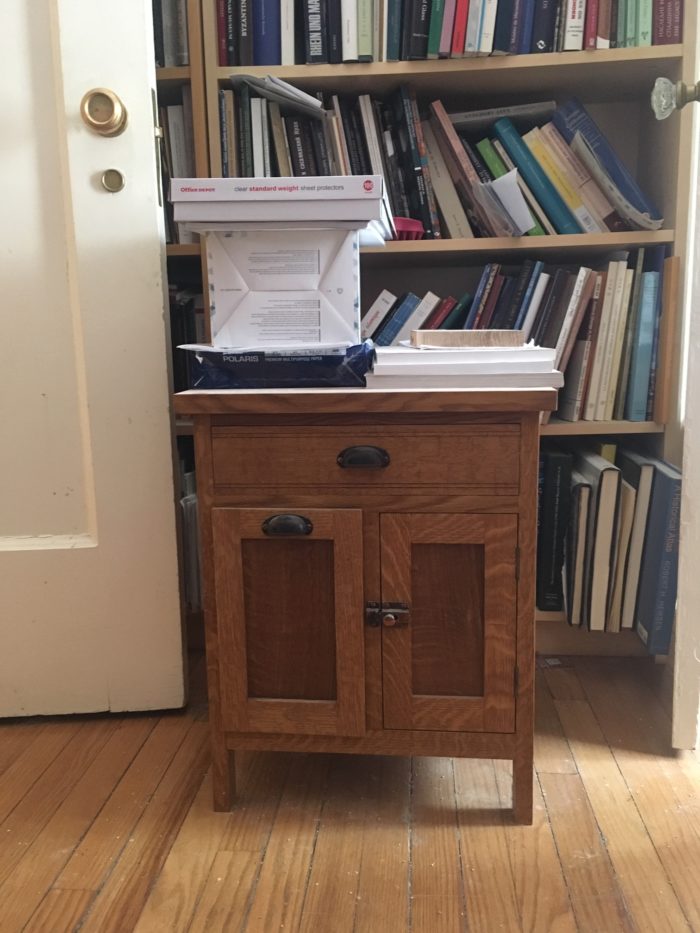

Often, I find that clients come to me for surprising and delightful pieces it would never occur to me to build, such as a turn-of-the-century baker’s cabinet I was commissioned to make several years ago based on a barely perceptible original in a photo of my client’s great-grandmother. A few years later the same client commissioned a smaller-scale version as a gift for her mother. That turned out to be one of the sweetest pieces I have ever built.

This brings me to another point I value about custom work: It’s other-centric. Instead of indulging myself, I serve others. I work closely with my clients to discuss materials and design, informing them of pros and cons along the way. Clients can be more than buyers; I treat most of mine as collaborators on their project. Almost invariably I meet with them in their homes, in order to get a good sense of their aesthetic and how they live—both of which are important to genuinely custom work. As someone who spends the majority of her working time alone, I appreciate this contact with other people.

Finally (for this section), one point about custom work that gets virtually no press is that it offers opportunities to restore trust in one another. I will never forget the moment my former employee, Daniel O’Grady, and I knocked on our clients’ door in Washington, D.C., with their new kitchen cabinets, which we’d driven to the nation’s capital from Indiana the day before. “It really worked!” exclaimed one of the clients. After having two site visits from me, following up with emails and phone calls, and paying a sizable chunk of money to my business as a deposit, she was thrilled to see our months-long collaboration finally about to make her dream materialize. To be a partner in a project that restores that kind of trust in other people is an honor.

Use spec work to solidify your preferred styles

Whenever I can afford the time and materials to do so, I build a spec piece that I want to build. Some of these have turned into published articles; others have simply helped build my portfolio. Aside from offering a refreshing opportunity to work in styles I love, these spec pieces have been my primary means to fleshing out the identity I talked about above. As people see the kinds of work I really love to do for its own sake—whether they see it at a friend’s house, on social media, at a gallery show, or in a magazine—they associate me increasingly with the kind of work I want. This helps me get commissions for the kind of work I love to do.

Nancy Hiller is a professional cabinetmaker who has operated NR Hiller Design, Inc. since 1995. Her most recent books are English Arts & Crafts Furniture and Making Things Work, both available at Nancy’s website.

|

|

|

|

|

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Drafting Tools

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Comments

Beautiful work. As a hobbyist, I have to try really hard not to be discouraged! I'll never do work on this level, but probably can appreciate it more than most non-woodworkers.

I bet your work is far better than you imagine it to be. (And no, this is not patronizing. I'm speaking from personal experience.)

My grandparents loved to collect antique furniture. If you had shown me the picture of the baker’s cabinet, I’d have sworn they had the same thing in their house - great work, I love it!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in