Synopsis: Allan J. Boardman, an aerospace systems engineer and amateur woodworker, evaluates the dimensional tolerances inherent in fine cabinetry joints. He talks about precision — in marking your work, cutting it, fitting it, gluing it, and more. He details tool quality, measuring, marking, cutting to the line, the benefits of using jigs, and when to let up on yourself in the pursuit of perfection.

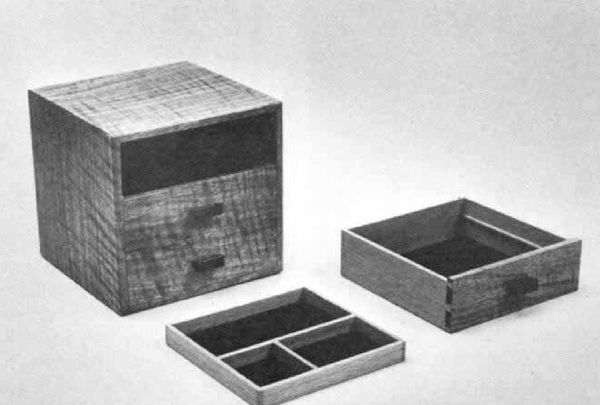

Comparing a machine tool such as a lathe for shaping metal with its counterpart for working wood suggests that entirely different methods and standards are normally applied when operating on these two dissimilar materials. The differences are obvious—finely graduated scales and dials festoon the metal lathe, while the wood lathe probably has no measuring scales at all. What may not be obvious is the fact that woodworkers nonetheless do approach tolerances that might seem appropriate only to metal. The flexibility and compressibility of wood, the acceptability of fillers, moldings and bulk-strength adhesives, the dynamic movement of the material and the omnipresence of shoddy commercial products all contribute to the belief that “precision” is not a word in the woodworker’s vocabulary. However, a close look at a truly fine piece of cabinetry will reveal some surprising facts about the dimensional tolerances inherent in its joinery.

Consider the miter joint connecting two adjacent members of a frame made from 3-in. wide stock (figure 1). If the miter were tight at one end and open, say, 1/64 in. (0.016 in.) at the other, the joint would be quite unacceptable. The frame would be weak, since most adhesives work best in films far thinner than 1/64 in. Even an untrained eye could easily detect the mismatch, and filler could not disguise it. Most shops have lots of clamps, and all too often they are used in abundance to bend or press a joint closed while the glue dries. The result may well be a tight joint, but the structure is liable to be distorted—warped, bowed or out-of-square. This distortion may cause extra work in fitting for doors or drawers, perhaps some unanticipated cosmetic repairs, or it may even be uncorrectable and quite obvious in the finished product. And regardless of how well one compensates, the assembly will retain residual stress after the clamps are released. Built-in stress will work against the adhesive for a long time, causing the joints to creep and the dimensions to change. Stress can burst open an otherwise strong joint months or even years later. Improperly seasoned wood and changing humidity, although usually contributory, are sometimes blamed for joint failure when the real problem is faulty joinery initially hidden by clamping pressure. In first-class work, there is no substitute for joints that fit properly.

In figure 1, note that the angle of the tapered space in the miter joint is less than a fifth of a degree.

From Fine Woodworking #25

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Marking knife: Hock Double-Bevel Violin Knife, 3/4 in.

Starrett 12-in. combination square

Comments

The PDF has two pages that are for some reason unreadable

Bummer. I am very interested in this article, but the PDF format is unreadable.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in