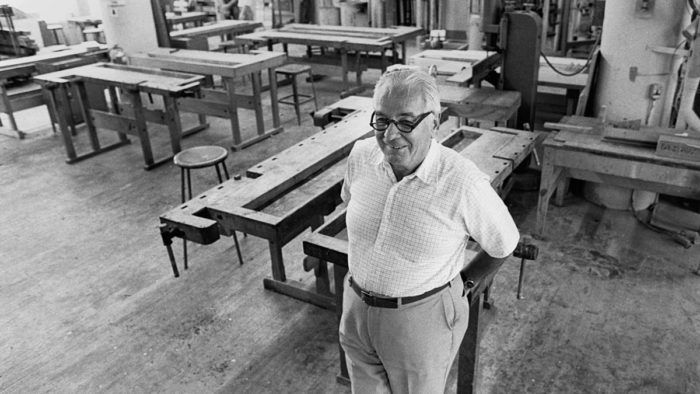

Professor Frid

A former student of Tage Frid describes the extraordinary experience of being taught by the Danish master

Editor’s note: Several months ago we asked Hank Gilpin if he would write something about his mentor, Tage Frid. Over the next few weeks we received a stream of postcards- Gilpin’s favorite mode of communication-and we’ve reprinted them here. Gilpin, 54, now one of the country’s top furniture makers, studied under Frid at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in the early 1970s and worked in Frid’s shop for a time after graduation. Gilpin caught Frid in the middle of a teaching career-spent primarily at Rochester Institute of Technology and RISD-that stretched from 1948 to 1985 and spawned scores of woodworkers who became prominent in the field. Along with superior craftsmen, Frid’s classroom also produced many of the best teachers of the next generation. The range of Frid’s influence increased even more when he began writing for Fine Woodworking. He has been a contributing editor to the magazine since the first issue and also wrote a trilogy of best-selling books for The Taunton Press.

Professor Frid walked into the shop dressed in a coat and tie, his thick, white, wavy hair perfect. He hung up his coat, rolled up his sleeves and tucked his tie into his shirt. He then turned and walked out of the shop into the alley. It was the first day of class, a basic woodshop course I’d opted for on a whim. A photography student, I had no real background in wood, but I needed an elective.

We could see Professor Frid through the open door, working with a mysterious contraption, something with a long tube all connected to pipes. He reentered the shop wearing canvas gloves and holding a long, skinny, steaming piece of wood. He quickly and purposefully walked to the front of the assembled students, said something I couldn’t understand and proceeded to tie the steaming stick of wood into an overhand knot. Just like that, my life’s path took a radical bend.

Danish vaudeville

Early that semester, Professor Frid was giving the dovetail demonstration. He described the process very quickly in his thick, Danish-accented English, simultaneously joking with the guys and flirting with the women. So of course no one had a clue what he was talking about. It was like vaudeville, really. He was gauging and scribing and marking while mumbling something about tails and pins and half blind and half pins, still cracking jokes and fixing his tie. He made each cut in three quick strokes with a 3-ft. bowsaw, slapped down the wood, clamped it, dragged a chisel across it, chopped away some waste and then repeated the same actions on the next piece, which he’d marked off the first in a flurry of pencil swipes. He looked at us speculatively over the rims of his glasses, picked up the two pieces of wood and triumphantly tapped them together in a perfect fit. Some of us applauded; others backed away in awe. What a moment!

The simplest solution

Carcase dovetails were always difficult: wide boards, hard wood, lots of pins and tails. Putting glue on all the pins and tails took way too long, and then there was the peculiar problem of clamping.

Professor Frid was watching one of these exercises in bumbling futility—glue dripping, glue drying, odd clamping blocks and a tangled tonnage of clamps. He approached the chaos and told us to get rid of the clamps. He grabbed a hammer, a small block of wood and, laying the carcase on its side, proceeded to hammer the joints together, seating each tail with a single, precise blow. He repeated the process on the other side and quickly moved to another dilemma brewing across the shop.

What didn’t he know?

Thursday morning was question-and-answer time in the shop. I was new to the field, and I’d spend hours in the RISD library, studying the history of furniture. A long list of technical questions piled up over the course of a week. Professor Frid agreed to sit down (which he really wasn’t inclined to do, being a very energetic fellow) and patiently go over my list, one question at a time. He always had an immediate and clear answer. No period, style or technique stumped him. More often than not he’d have two different technical solutions to offer: one of old tradition, focused on old tools and old technology, and the other emphasizing recent innovations in tools, machines, glues and finishes. He’d talk of animal glues and epoxy, chip carving and routers, hammer veneering and plastic laminate, French polish and spray lacquer, rasps and shapers. His knowledge seemed encyclopedic, felt experiential and was unbelievably valuable to me, a rank beginner who was falling under the spell of this amazing man.

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Originally published in our 25th anniversary issue, in 2001.

More on FineWoodworking.com:

- Veneering Over a Solid-Wood Substrate – Thirty-year old rosewood gives life to a shapely coffee table

- How to Make Drawers – Design for drawing table illustrates the principles

- Three Decorative Joints – Emphasize the outlines with contrasting veneers and splines

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Blackwing Pencils

Sketchup Class

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Comments

Fantastic piece of writing (despite the origin in postcards...;) ). Such a vivid portrait of Frid. You can see exactly why all these students had such affection and respect for him.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in