The Mighty Wedge

Fixed or loose, wedged joinery adds strength and style

Synopsis: Wedged mortise-and-tenon joinery is a low-tech but effective method of joining wood, and it evokes a sense of timeless craftsmanship matched only by dovetails and other exposed joinery. In this article, furniture maker John Nesset details various methods and applications for using wedges in your joinery. Drawings and his detailed guidelines on grain orientation, appropriate angles for wedges and relief cuts, and installation will help you feel confident about using loose or fixed wedges in your next project.

From Fine Woodworking #163

Since antiquity, wedges have served as an important means of joining wood. Low-tech but effective, they remain a useful and attractive element of joinery, evoking a rustic past when life (we like to think) was simpler and more straightforward. Like dovetails and other exposed joinery, wedges convey a sense of solid, honest craftsmanship, even to the uninitiated.

A whole book might not be enough to detail every application for the mighty wedge, but I’ll cover the two major types in their basic single and double forms. From there, furniture makers can derive other variations.

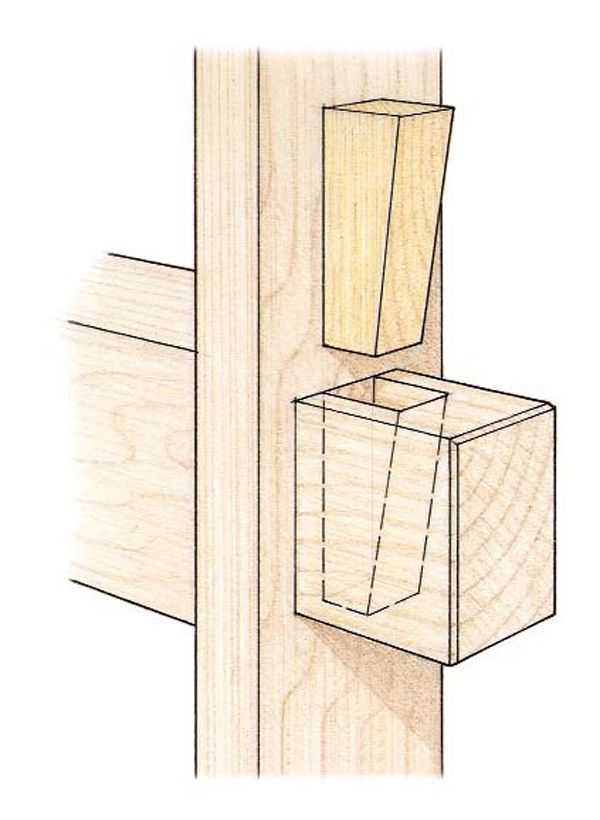

Wedges fall into two general categories: fixed and loose. Both types are driven into through-tenons to reinforce the joint. Fixed wedges generally are driven into the end grain of a tenon with glue added for reinforcement, then trimmed flush. They are appropriate where the wedge risks working loose.

Loose wedges are driven into a mortise that goes crossways through a protruding tenon. Loose wedges are not glued or fastened, so they must be oriented so that gravity and/or friction will keep them in place. They are used for two reasons: to create a knockdown joint and for decorative effect.

Whichever wedge type you choose for your project, you must take into account grain direction. The hard-and-fast rule is that a wedge must be oriented in the mortise so that it applies pressure against the grain, not across it. As young Abraham Lincoln demonstrated in his famous fence-building project, pressure applied across the grain splits the wood. In the case of fixed wedges, this fact of life will determine whether you need a single wedge or double wedges.

It’s worth spilling some extra ink about this first type of wedge, as it will illustrate many of the general principles for all wedged joints. For example, for any of these wedged joints, start with a carefully fitted, square mortise and tenon. For a fixed wedge (or wedges), leave the tenon just a little long, so it protrudes from the mortise 1⁄4 in. or so.

The most important thing to know about wedges, fixed or loose, is to cut them at an angle of 5° or less. In this range, friction alone will hold the wedge to the tenon. Also, if the two halves of the tenon are bent too far by a thick fixed wedge, they will be weakened at the base, thus weakening the joint. Of course, wedges driven into the end grain of a tenon will be subjected to pressure (from racking forces and seasonal expansion and contraction) that would overwhelm friction alone, which is why the bond should be strengthened with glue.

For the full article, download the PDF below.

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Freud Super Dado Saw Blade Set 8" x 5/8" Bore

Festool DF 500 Q-Set Domino Joiner

Sketchup Class

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in