A Joint that Exploits Wood Movement

Traditional wet/dry joinery uses heat and moisture to strengthen a post-and-rung connection

For most woodworkers, wood’s tendency to expand and contract with changes in moisture content is a burden that must be borne. Ignore this movement when designing and building furniture, and sooner or later, boards will split and joints will fail.

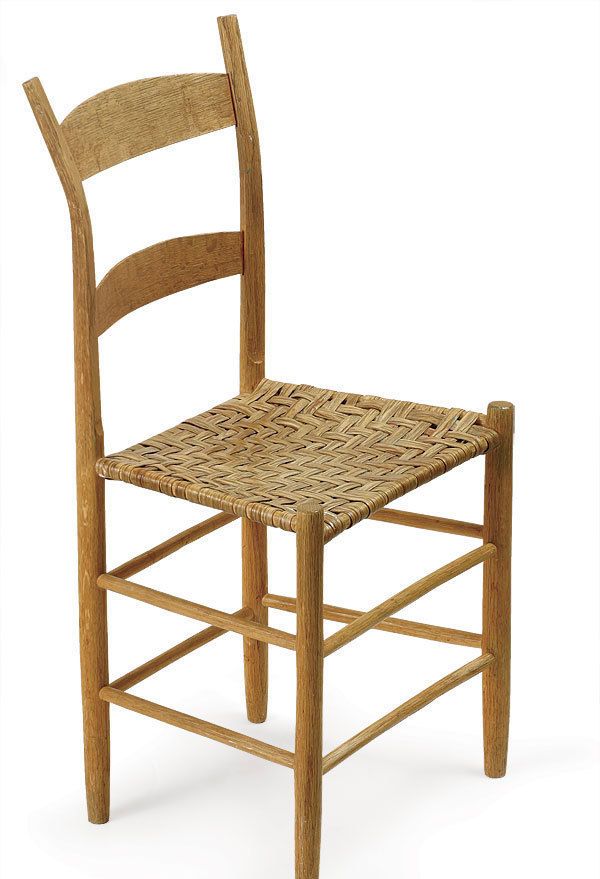

However, there is a small corner of woodworking that for centuries has exploited this characteristic of wood. By harnessing wood movement, an 18th-century post-and-rung chair can remain rock solid while the joints in modern reproductions fail. The secret is commonly known as the wet/dry joint, but more accurately as the moist/bone-dry joint. Generations of chair-makers have relied on this joint to hold together both traditional post-and-rung and Windsor chairs.

How wood movement creates tight joints

The essence of the joint is a bone-dry, slightly oversize tenon driven into a mortised post that is slightly moist and compressible enough to accept the tenon without splitting. The tenon’s rays are oriented parallel to the direction of the post’s long fibers. In this way the joint takes advantage of wood’s unique movement in response to moisture change in each of its three axes. Wood does not shrink or swell in the direction of its long fibers; the height of the mortise and the length of the tenon do not change. The movement happens along the other two axes: about twice as much in the direction of the transverse or growth-ring plane as in the radial or ray plane.

After assembly, the tenon absorbs moisture and its top and bottom swell slightly along its radial plane and bond against the mortise. The main movement in both tenon and post is in the width or growth-ring plane. As the two parts of the joint reach even moisture, the tenon has swollen in width and the mortise has shrunk around it. The tenon sides are flattened before assembly so these powerful opposing movements don’t split the post.

A brief guide to making this joint

Use straight-grained hardwoods such as oak, hickory, ash, maple, or beech that are split (rived) along the grain from green logs or boards. The straight grain of riven pieces gives critical strength.

Get the right moisture in the mortise—While the rung stock must be bone dry, the posts need to have about 5% more moisture than the ultimate moisture content of the joint after assembly and drying. In Baltimore, the ultimate moisture content averages about 10%, so I want the posts at 15% at the time of assembly. Because a post dries much faster on its surface, it is difficult to measure this crucial interior moisture content with a moisture meter. rather than create extra post stock (to split open), gauge the diameter of a typical green-wood post on its growth-ring plane halfway down its length. Mark this location. Slowly kiln-dry all the posts at 100°F and regularly check the diameter of the marked post. when its cross section begins to shrink and the gauge becomes loose, the marked post has lost all of its free water and has a moisture content of approximately 28%. weigh all the posts and then continue to dry them until they have lost 13% more weight. The posts will be oval in cross section and will have an approximate moisture content of 15%.

Dry the rungs. Because the rungs must be bone dry when inserted into the posts, a homemade kiln with heat lamps is used to dry them. |

Dry and tenon the rungs—Clearly mark the rung stock at both ends with a centerline in the direction of the ray plane. In the joint, this line will be vertical and parallel to the long fibers of the post. The tenons of rived green stock are first drawknifed to a 3/4-in. square whose sides are parallel to the centerline, then to an octagonal cross section that just fits into a 3/4-in.-dia. circle. dry the rungs at 125°F and weigh them together until they stop losing weight. They are now bone-dry at less than 6% moisture content. Mark your tenon length with a light pencil mark and slightly flatten the tenon sides with knife cuts parallel to the ray plane centerline. Carefully shave the tenon’s upper and lower domes until the tenon can be forcibly rotated by hand about 3/32 in. down into a 5/8-in., bone-dry test hole bored in the same wood as the posts. reject all rungs with loose-fitting tenons. return each rung to the kiln when it has been tenoned.

Drill the mortises and assemble the joints—Bore the side-frame mortises first. glue isn’t necessary but will substantially increase joint strength. Assemble the side frames by pounding the tenons home with a slightly round-faced hammer or a mallet. The tenon ray plane centerlines must be parallel to the direction of the post’s long fibers.

After assembling the side frames, the front and rear frame mortises are bored so they interlock 3/32 in. up into the side frame tenons. In post-and-rung construction, the most common failure is side-tenon withdrawal due to fore-and-aft racking forces. The interlock opposes this. Assemble the remainder of the frame.

For more than 30 years, my students and I have made thousands of successful, lasting joints, each proving that the moist/bone-dry joint is superior to those joints assembled with their mortise and tenon at the same moisture content.

Photos: Mark Schofield; drawing: Rodney Diaz

From Fine Woodworking #184

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Marking knife: Hock Double-Bevel Violin Knife, 3/4 in.

AnchorSeal Log and Lumber End-Grain Sealer

Festool DF 500 Q-Set Domino Joiner

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in