Most finishers have probably experimented with mixtures of boiled linseed oil and varnish in an attempt to produce a better finishing material than either oil or varnish alone. Whether the resulting finish is really better depends on what is needed in terms of drying time, hardness, luster and film build. Because no information exists on the properties of specific mixtures of varnish and drying oils, the finisher must continue to experiment. To give the would-be experimenter some data on which to base the experiments, I ran a series of tests under controlled conditions, eliminating as many variables as possible.

The oil/varnish homebrew mix – I chose a typical soya alkyd varnish (because most varnishes on the market are of this type) and a commercial boiled linseed oil as the base ingredients. I blended the varnish and oil samples into mixtures of the following proportions: 100% varnish, 90% varnish/10% oil, 80%/20%, 60%/40%, 40%/60%, 20%/80%, 10%/90% and 100% boiled linseed oil. The 100% varnish and 100% oil samples were the standards against which I compared the various mixtures. The 90%/10% varnish-to-oil and oil-to-varnish mixtures were used to determine how a mere trace of oil changed the properties of pure varnish, and vice versa. The other formulations were varied by 20% steps to keep the total number of test mixtures manageable.

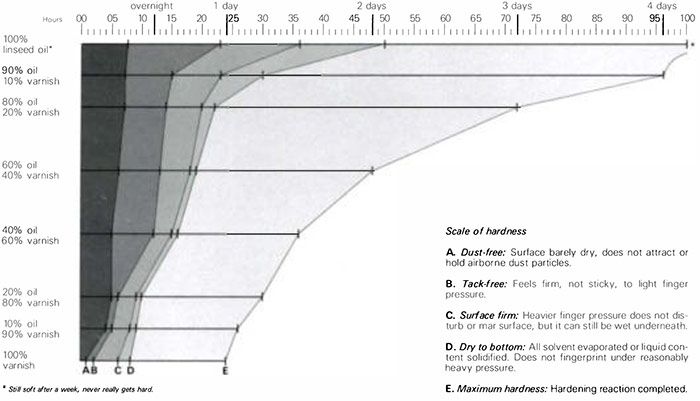

I drew out each of the mixtures on a piece of chemically clean glass to a uniform wet film .009 in. thick. The drying times are shown in the table above. The only real surprise was that the addition of 10% boiled linseed oil to varnish produced a substantially softer film than one might expect, and that a 10% addition of varnish to oil produced a harder film. In the other mixtures, each material’s properties were modified by the other’s properties to about the same degree as the amount of each component present. In practice, this means the more oil you add to the varnish, the slower the film will dry and the softer it will remain.

Although I evaluated alkyd varnish and boiled linseed oil, any drying oil can be mixed successfully with varnish. Polyurethane and phenolic varnishes will work well in place of alkyd types, as will tung oil in place of linseed. But whatever the makeup of a given mixture, its overall properties will probably vary as the proportions of its components vary.

Only experimentation will provide answers. However, a 50%/50% mix of whatever components the finisher chooses is an excellent starting point. Chances are the finisher will never need to experiment with other proportions.

I didn’t use thinner in testing because it would have introduced a variable without changing the ultimate results. In actual finishing, however, such mixes are often thinned with either mineral spirits or turpentine.

Thinning helps the first coat penetrate the raw wood and seal its pores, but probably has no effect on subsequent coats. In most cases, the thinner present in the varnish as it comes from the can provides adequate penetration. But if you want to thin the first coat, mix equal pans of thinner and oil/varnish mix. Keep in mind that the more a mixture is thinned, the lower the solids (film-building) content. Consequently, you’ll need more coats of a thinned mixture to produce the same film thickness as an unthinned mixture.

As mentioned, tung oil may be used to replace boiled linseed oil in the oil/varnish homebrew mix, and in fact it will produce results superior to linseed. To this end, I ran another test comparing a 50%/50% mix of polymerized tung oil and the same alkyd varnish. Chart 2 shows the results. Though the tung/varnish mix remained fluid long enough to rub out well under hand pressure, the film dried hard all the way through in the same period of time it took the linseed /varnish mix to become only tacky.

From Fine Woodworking #19

From Fine Woodworking #19

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Osmo Polyx-Oil

Bumblechutes Bee’Nooba Wax

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in