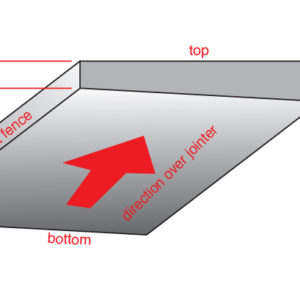

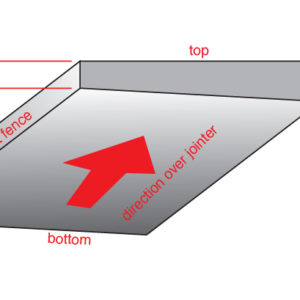

My jointer is not cutting square with the fence. See the attached illustration, hopefully this will give you a better idea of the problem. If I take a piece of wood 3/4″ thick and run it across the jointer a few times, I’m left with the wood being 3/8″ thick on one side and 1/2″ thick on the other.

I’ve checked to see if the fence is square to the tables about 73 times. The blades appear to be level with the outfeed table.

What am I missing here? Could it be something that I’m doing wrong? Maybe I need a new square?

Any help would be appreciated.

Replies

I had a similar problem with my jointer (Old 8" Delta). After much frustration, I decided to start from scratch. I had the blades sharpened by a local expert, took the machine apart, checked belt alignment, tension, cleaned everything up and put it back together. Went thru a long process of making sure the infeed and outfeed tables were parallel, and in the same plane with each other. Then, reinstalled the blades, and made sure they were dead level with the outfeed fence front to back. I had purchased one of those magnet blade setting devices which proved totally useless. Did it with the straight edge ruler out of my combination square.

Started it up and ran a test piece of 2" x 8" red oak, and Oh my god, what a difference. I don't know what fixed the problem, but now I have one sweet machine.

Do you have the operation manual with your machine. Usually they have instructions for tuning your machine. I am attaching a "How to Tune your Jointer" article I found in some magazine, maybe FWW

Good luck, Jim

Every shop needs a good 6" engineers square for setting up and checking equipment. They are not very expensive. Without accurate measurement tools, you won't know if you are actually square. I don't think this is your problem.

The picture you showed depicts face surfacing. In this operation the fence doesn't serve any function other than to keep the piece from running off the machine. You do not reference a face by putting the edge on the fence. It's just the opposite. You put the face against the fence to square the edge. Simply putting an accurate square on the infeed table close to the blades will tell if the fence is square to the table.

When you use a jointer, there are some things that make logical sense but the jointer doesn't always cut logically. You would think that if the machine is set up properly and an edge is straight, that you could make a dozen passes and each one would take off a perfectly equal amount. What actually happens with many passes on a jointer is that it tapers the work. The same thing can happen with a face. Take a flat planed 3/4" board and run the face for several passes. The piece may taper from side to side as your picture shows and it can also taper end to end. This "phenomenon" can be worse when the user tries to take very fine cuts, like 1/32" and less. The combination of making extra passes with a fine cut beats the devil out of your knives, too.This may be all that you are experiencing, too many passes.

Jointers are pretty simple machines but little discrepancies in the set up can cause problems. The way a person operates the jointer can also make a big difference in the results. I think you already have most of the technical stuff down about set up but you might be over doing it on the cuts and expecting the jointer to be logical.

Beat it to fit / Paint it to match

Very interesting, Hammer. You hit the nail on the head.I actually used the face jointing scenario here because I noticed this was happening, and it is more pronounced when cutting the face. Normally I just pass it through my planer.But you are correct, I have been making multiple passes with very shallow cuts. I think I started doing this because it is sometimes difficult to determine the direction of the grain. If I jointed an edge and it chipped out badly, I'd just turn the board and run it the other way. So I thought I'd make several shallow passes rather than one deep pass to keep from tearing up the board badly.I've spent countless hours trying to set up the machine, when it seems it was operator error all along. This tapering effect is illogical, I'd like to have someone explain the physics behind this.Thanks for your help.Jeff

I know very little about jointers, so I could be way off here. But isn't the only way you could end up with this situation is to have the cutterhead out of parallel with the beds?

As someone else noted, when face jointing the fence does serve to keep the stock square to anything. The stock moves along a (presumably) flat bed, passes over a cutter that is spinning parallel to the bed and the outfeed bed itself serves as the reference. Get either the infeed, outfeed or cutter head out of alignment and you would get your situation of a wedge.

Hope the British terminology of "planer" (you say jointer) and "thicknesser" (you say planer) is not confusing here......

When you begin to plane (joint) a board with a bumpy surface, some of those bumps determine how the board travels across the planer bed and knives on the first pass. Depending on where those bumps lie and how you press on the board as it travels, the board will begin to flatten in a particular "horizontal" plane (oh dear, this is going to get confusing).

If that plane happens to be tilted towards the left or right edge of the board by the bumps/your feed style, then the board will end up wedge-shaped, as your photo shows. Perhaps you yourself tend to press on the board towards the fence, rather than the middle, as you feed it across the table; so that the first pass has the board riding on fence-side bumps?

If a board is more or less concave on one side and convex on the other, start on the concave side. This helps to keep the board flat on the bed as it rides on the two edges and/or the board ends. Of course, some awkward boards are concave down their length on one side but convex across their width on that same side. Rascals!

It's also possible to plane with too much of your weight on the front end of a bowed board. Then you get the wedge going down the board - a thin front with a fat back end.

Me, I've planed boards into various wedge shapes in my time and learnt the hard way. Doh! The answer is correct feed technique along with an understanding of why the cut is happening as it is.

So, plane convex side first, keep your weight in the centre of the board just behind the blades. Watch for any tendency to wedge one way or another and apply compensating pressure or feed to right it. But it's best to try and make the first cut an even one, taking bumps evenly off the whole width and length of the board. It's the first cut where any wedging starts, then each subsequent cut amplifies the wedge.

One last point (sorry for rambling on). You don't need to get every bump and hollow out of one side of a board before you put it to the thicknesser. You just need it to have enough flat bits to keep it travelling in the same plane across the thicknesser's bed. Once the thichknesser has flattened the unplaned side of the board (and hopefully not curved the board along its length) you can turn it over in the thicknesser and take out the remaining bumps/hollows in the planed side.

I've had the same experience (we all have I think).

If a board has a significant twist or wind, you can end up tapering it. One way to avoid this is to follow the advice that Hammer outlines, with one additional point: if you notice a taper, alternate your passes. That is, if face planing, keep the same face down on each pass, but feed one end first on one pass, and the other end on the next pass.

Tear out is not as big a problem as you might imagine. If the jointer knives are sharp, it won't be a big issue except on highly figured wood. Once you have the twist under control, you can go back to feeding the board with the grain properly oriented, or just clean up the problem on the planer (thicknesser). I've said it a few times on this site: a jointer is designed to give you a flat face and a flat edge at 90 degrees from each other. Don't be looking for no mirror finishes...

If a board has a real major wind in it, and you want to mill it anyway, scrub down with a handplane first. Once it will sit on your jointer bed without rocking you can mill it just fine. It'll take less time and frustration than trying to do it all on the machine...Glaucon

If you don't think too good, then don't think too much...

Glaucon, so are you saying it is possible (common) to get a wedge that runs the length of the piece due to twist? I think I'm envisioning what you are getting at, but I'd never thought of that. As I said, I've had only minimal jointer experience. Such a simple, basic machine, but very subtle things can give you not so subtle results.

JH

The simplest case to think about is a situation where one end of the board has deeper cuts taken from it than the other. If one end is cupped and the other is not and if the part in between is saddle shaped (at ~ 90 degrees from the cupping), then jointing the board may cause the cupped end to have a deeper bite taken from it than the opposite end. Each succeeding pass will exagerate the problem, and you will taper the board. The amount of cup/saddle does not have to be too great for this to happen, Very tiny increments on the jointer (~1/64") may make this worse as the asymmetric end will be shaved, but the other end may not be- leading to many more passes and thus tapering.

If you notice tapering, the first sign is the sense that only one end of the board is being shaved. You can watch for this by chalking the face that is being jointed and making sure that you are actually progressively working the whole board.

If you start to taper, joint one end first, than the other or knock down the high points to semi flat with a scrub (hand) plane.Glaucon

If you don't think too good, then don't think too much...

Glaucon, looking at the original post, I'm wondering if what you are describing is applicable though. If I were to assume that he is getting a clean face and consistent thickness from end to end, but with faces significantly out of parallel would what you are describing still be relevant?

Envisioning your description I would assume you would get a taper from end to end, and side to side, but not consistent along the length of the board. Or am I missing something?

Jake

Just wanted to thank everyone here for their input. I went through the jointer, making sure everything is square and set up as correct as I can get it.I started a new project yesterday which required edge joining several pieces. The jointer seemed to cut perfectly on these edges. I have not tried face planing anything yet, but everyone's info above has been very helpful. Thanks again.

If you run a board through in a series of passes in one direction, you'll be able to see if it's out of alognment. If you reverse it after every pass and go each way the same # of passes, any error will cancel. Run a piece through multiple times and don't worry about tearout. If there is any error, it will add to the previous errors and it will be obvious. Assuming the knives are parallel to the outfeed table, any mis-alignment will probably come from the infeed table. Look in your manual for setup instructions concerning jib screws.It's more a matter of geometry than physics. If you run the board through in one direction and there's .01" tilt, the error will become .02" after 2 passes, and so on. It's not a lot but it makes for big problems when trying to achieve any accuracy. It doesn't take much time to mill a wedge when a jointer is out of adjustment. Mine is doing the same thing after having the knives sharpened and I just couldn't leave it alone- I tried it out and thought "I should be able to make it work even better" after putting a straightedge across the tables. Now, I just need to find time to set it up again.DOH!!!!.

"I cut this piece four times and it's still too short."

Hi Jeff,

I don't know that I can explain why jointers and other woodworking tools do what they do. Like many things, a little here and a little there all of a sudden start adding up. The wood is a natural substance, hard in some places, soft in others. Your hand pressure is bound to change, the knives will deflect, and dull. When going through the milling process, we flatten a face on the jointer, plane it to thickness, straighten one edge and then rip it to width on the saw. Often we return to the jointer to clean up that ripped edge. When we make this pass, it's a sizing cut, not a straightening cut. Instead of transferring hand pressure from the infeed to the outfeed, you keep pressure on both tables. After all, the piece is already straight. You can usually be successful if you only make one pass. Make two or three and you will likely see the tapering. I can only imagine all the forces that are involved from electrical input to the cut on the board. You have deflection in all the moving parts from bearings and belts to the edge of the knife. If you check the height of new blades with a micrometer and check again after some use, you will see that things have changed. If you set your knives perfectly even with the outfeed table, the jointer won't work correctly. You have to allow a bit extra. This is only one of the components. Another way to see some of this is to run the edge of a board fairly fast across the jointer. You will see pronounced knife marks, just like the edges of most pre-milled common lumber at the supplier. You can't see it or feel it happening, but the marks on the wood will clearly show that the piece has been bouncing up and down during the pass. Slow down and you get what appears to be a nice unmarked surface. Put that edge under a microscope and the scallop marks are there, we just can't see them with the naked eye. At the microscopic level, there is incredible violence and chaos going on.If you think about how knives and cutters do their work, a lot of it is right at the very edge of the weakest point. A skimming cut puts all the stress on this point. I think if you could watch a video of the action in slow motion, you would see that the first knife engages the wood and takes a cut, The knife has met resistance and the second knife takes off a little more of what the first one left. By the time the third knife spins around, it may not be sharp enough to actually engage the wood and just rubs on the stock, probably lifting it and in the worst case, burning the edge. If you add in a little slop in the bearings, deflection in the cutter head and shaft, account for the variety of density in the wood, don't forget heat and friction, it can give you an idea why the jointer and other woodworking cutters don't live in a finite mathematical world. All the issues I've discussed are those that can occur when the machine is set up properly and the operator knows how to deal with rough lumber. If the blades are set at different heights or out of level with the tables or the operator rocks or twists the work, the same things will happen, but worse. I taught woodworking and a common thing among students was making unnecessary passes and trying to cut micrometer amounts. The harder they tried for perfection, the more elusive it became. Their reasoning was based on the jointer or the saw blade, etc. and their hand being perfect every time. That's what makes woodworking so interesting and perfect joinery so challenging, hand or machine.Beat it to fit / Paint it to match

It could be something as simple as having a knife set high on one end of the cutter head.

Ron

Just one more reply that might solve your problem. A jointer is usually used more for edge work than anything else and we sometimes use the fence in its right hand position for this. It saves our having to adjust it when we do face work. However, one should vary the fence position often for edge work so as to spread the wear across the entire length of the knives. If the knives are dull on one half their length and sharp on their other half, then the result you speak of may occur.

This forum post is now archived. Commenting has been disabled