I dialed Sam Maloof’s number timidly in 2005, just another writer calling for a piece of the icon. My idea was to do a twist on the typical Maloof homage, asking him instead to offer advice to aspiring designer/makers. His longtime assistant, Roz Bock, put my call through and suddenly I was talking to the man. He was friendly and open right away, even though I was a stranger. He said he wasn’t sure if he had much to say to guide others, but he was game to try.

When I turned into the driveway of Maloof’s famed compound a few months later and found his office, he was just as down-to-earth and accommodating in person. During the two days I spent with him, we were interrupted regularly by visitors. All were welcomed, given a tour, and given plenty of his time. I know this drove his staff nuts, because it left his daily schedule in tatters and did nothing to shorten his multiyear backlist, but it made him universally loved. I am just one of hundreds who visited with Maloof and came away changed.

Strong in his 80s

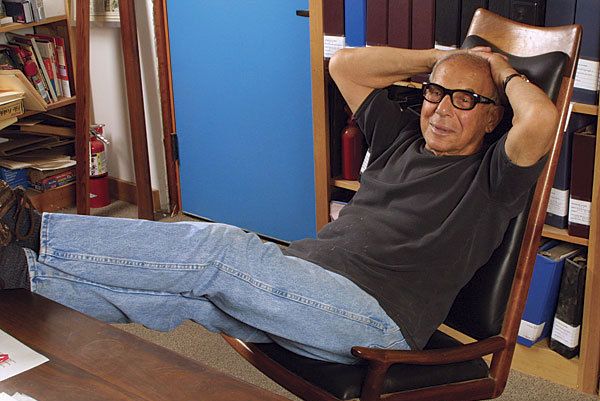

At 89, Maloof still insisted on doing at least the rough shaping on all of his chair parts, muscling them sure-handedly across the bandsaw table. And he moved with the grace of a much younger man through the various construction projects on his sloped property, where ground was being cleared for a public gallery. He drove me to lunch the first day in a brand-new Porsche convertible. He did about 85 mph, chatted constantly, and ran over a few road cones while he reached for his cell phone. It was a slightly surreal ride in the California sun.

I was humbled when he left me alone in his old house for a day of uninterrupted shooting. I gingerly moved my umbrella lights through his handmade doors, around the artwork of his famous friends, between iconic pieces of his furniture, through the life he and Alfreda had shared. Friends say Sam was never the same after she died in 1998. He moved out of the house, had it declared a historic landmark, and built a new one nearby.

|

|

In the weeks since Maloof passed, I’ve realized that he was the first real national treasure I’ve known. “National” is the right word because his was a uniquely American story. The son of Lebanese immigrants, he served in the Army, trusted his intuition always, became a unique entrepreneur, and made furniture for two U.S. presidents.

He made his own rules

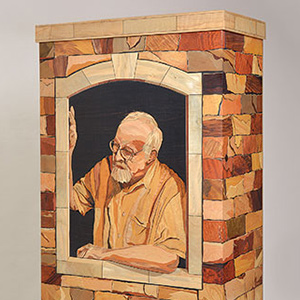

Even if he wasn’t such a charming man, his furniture would have made him famous. Being self-taught and one of the first of his kind, Maloof was free to make his own rules. When he found flush drawers tedious to fit, he recessed them in a rounded frame. When he needed curved parts, he balanced them on the bandsaw table, making free-form cuts that would torture the most lenient shop teacher. He put screws in his joints, used sapwood, and sanded through laminations, but he built his pieces one at a time, letting each develop a life of its own. And they’ve proven almost impossible to copy. I’ve never seen an accurate reproduction of his rocker. Try matching the sinuous crest rail, with its complex interplay of hard lines and soft surfaces, draped curves, and tight arcs—his three staff craftsmen can do it, but they’ve been with him for decades. Maloof repeated a handful of pieces again and again, but was always making improvements, so every new version contained all of his skill and experience.

After spending a couple of days with the man and his furniture, I started to realize that one resembled the other: walnut-colored skin, a slightly bunched muscularity, even the desire to please. Maloof wanted clients to love their pieces. He put function above all else. He guaranteed all of his work and would take pieces back at any time for repairs.

Boundless creativity

It is an understatement to say the trip was inspiring. Like my other two favorite woodworkers—Wharton Esherick and George Nakashima—Maloof’s creativity didn’t stop at furniture. He created his world, surrounding himself with beauty and grace. His life, houses, art collection, techniques, furniture—everything from carved door handles to custom window frames to beautiful rooflines—all emanated from that same generous, inquisitive soul.

On the last day I was there, I worked briefly in Maloof’s new home, shooting a few rare pieces. When he came in for a midday nap, I tried to leave. But he insisted I stay and get what I needed. He was content to go to sleep as I moved around just outside his open door.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in