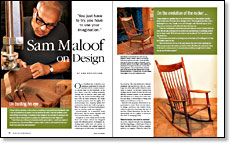

Sam Maloof on Design

"You just have to try, you have to use your imagination."

Fine Woodworking editor Asa Christiana spent a day with Sam Maloof at his California compound, talking about design and gathering advice for those who aspire to creating their own pieces. Read the full text of the article or become a member to download the PDF.

On a cloudless day on his four-acre California compound, 89-year-old Sam Maloof is in constant motion. He spends time on the bandsaw, as he does almost every day, making freehand, curving cuts on sinuous chair parts and table legs. He solves woodworking problems with his three assistants. He walks his sloped property with the agility of a much younger man, stepping lightly over construction debris and walls in progress.

When he speaks to his head maintenance man, he switches easily into Spanish. Around people, he is respectful, even affectionate. But he seems happiest and most focused when he is creating. Though he is most widely known for his chairs and rockers, Maloof has designed some 500 different pieces of furniture, including many tables and case pieces, as well as two homes. His original house, in a lemon grove in Alta Loma, was displaced by a freeway. The state declared it a historic landmark and moved it in 2001 to a new,larger site a few miles uphill, where it is now open to visitors. At the time, Maloof was dealing with the death of Freda, his wife and lifelong business partner, so he embraced the relocation as a chance for a new start.

For one thing, it allowed him to design and build a second house, to live in. Maloof’s new property offered lots of opportunities to create. There was the chance to design cavernous new lumber sheds, which he placed so they frame his view of the San Gabriel Mountains. He also has a spot picked out for a gallery to showcase the work of emerging artists. Talent is innate, but must be nurtured

As a boy, Maloof already was designing and drawing things, a sketch pad always at hand. His first serious job was as a graphic artist in Los Angeles. When he joined the Army during World War II, his superiors discovered his drawing skills and put him to work as a mapmaker. Today, after delivering pieces to the White House and the Smithsonian Institution, after being hailed as a national treasure, he still is sketching and designing, changing his furniture and surroundings, looking forward always.

It’s hard to pin down Maloof on the question of design. Basically, he knows beauty when he sees it. He believes that design can’t be taught—the talent is either there or it is not— but he allows that one’s innate talent can be nurtured. For woodworkers who wish to improve their design skills, he recommends frequent drawing and sketching. “I still do that. I think of something, and I’ll pick up a piece of paper, and I’ll do a sketch of it and put it in my pocket. And one idea begets another idea.”He also suggests exposure to art in all forms. Most of all, he recommends designing and making lots of pieces. To those who admire his work but are afraid to design their own, he says:

“You just have to try; you have to use your imagination.

“You have to ask yourself, ‘Do I just want to work in wood and copy beautiful objects?’ I see nothing wrong with copying, but how much more satisfaction do you get when you know you designed that piece, when it is your piece?”

Maloof also values the experience that blossoming woodworkers can have at schools or in other communities of peers. “I find that students are not selfish; they help one another and critique each other’s work. They feed on one another.”

However, he warns against domineering teachers: “Some instructors demand that you work the way they work, and so there become just many little followers of this person or that person. I see a lot of work where I can tell where that person went to school right off the bat. “I think a good teacher gives the whole rope to the students and lets them do what they want to do. I don’t think you should curtail the excitement or the invention or the new direction. Sometimes [the student] falls flat on his face; other times it’s great.”

Trust your instincts when creating, but put function before form

Maloof had no formal training in art or furniture making, so there is a completely personal quality to his work—polished yet unsophisticated—which strikes a chord in a wide range of people. Throughout his career, Maloof simply did what made sense to him, trusting his own eye and instincts at a time when the concept of the studio furniture maker didn’t exist.

Maloof’s design philosophy is deceptively simple: to make pieces that function well and are beautiful—or “byoodeeful,”as he says, referring to anything from a tree to a pottery vessel to a joinery detail. But function comes first. “I’ve seen tables that you couldn’t eat off of, chairs you couldn’t sit on, cabinets that were so shallow you couldn’t put a pair of socks in them,” Maloof says.

“They were beautifully made and nice to look at, but I felt a piece could be very beautiful and very functional at the same time, and that is really the center of what I do. I want my chairs to invite people to sit on them. This has been my objective since my first commission.”As for designers who consider sculpture or art first and function second, Maloof says, “It’s art furniture, and I think some of it is very interesting. I take my hat off to them. But to be different just to be different, though, is just a lot of poppycock.

“Some potters, they have a style and they stay to it. Other potters will continue changing—this direction, that direction. I heard a very well-known potter say, ‘I’ve got to figure out what’s going to sell good this next year.’ That is for the birds. I’ve chosen to do what I do and I try to do the best work I can. And every year I add two or three pieces to what I’ve done.”

From Fine Woodworking #179

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Dividers

Drafting Tools

Circle Guide

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in