An Illustrated Guide to Crown Moldings

Combine classic profiles to match any period or style

Take a tour through crown-molding history to discover the aesthetic and practical virtues it offers. This visual glossary of elements and representative pieces will help you develop the vernacular and the know-how to identify and reproduce accurate crown moldings in your own workshop. The article also shows how to use 21st-century methods to build a swan-neck molding.

Read the full article text:

Throughout the history of cabinetmaking, applied moldings have made substantial contributions to the aesthetic enhancement of case pieces. Combinations of cove, quarter-round, and ogee moldings reflect light and create shadows, adding a lot of visual interest to a piece. The crown, or cornice, also can have a practical function. For instance, I have seen them outfitted with secret drawers.

Without the horizontal finality of a crown molding or the lyrical interest that a broken pediment or a swan-neck pediment provides, the top of a case piece would stand without presence, creating a sense of lightness or weakness. In later periods, builders gave the top of a case piece the visual grounding by creating an assembly of elements known as the entablature, a term that comes from Greek and Roman architecture.

In furniture, the entablature is a composition of individual molding profiles at the top of the piece. The entablature, combined with a plain cornice or a complex broken pediment above, adds a feeling of weight, giving the eye another place to rest and another point of interest to explore.

How moldings define the period

As I gaze at a masterpiece of 18th-century furniture, my appreciation for it is two tiered. Initially, I am struck by an overall presence imparted by the size and proportion of the piece. Even an untrained eye can detect an ill-proportioned piece. When a piece looks right, it feels right, too.

Upon closer examination, my eye travels upward, along the piece’s lines and embellishment. I begin with the shape of a cabriole leg or base molding. I move on to the horizontal definition provided by the waist molding; it is a kind of aesthetic breather that prepares the eye for the vertical shift required to make a comfortable transition to the upper case. Finally, my eye is guided along the converging angled lines or sweeping curves of the pediment.

The first settlers in America brought with them European styles, such as William and Mary, Queen Anne, Chippendale, Hepplewhite, and Sheraton, which deeply influenced the furniture and architecture produced by early American craftsmen. When I look closely at the crown moldings of American furniture, I am compelled to interpret them in my own work. However, to make faithful reproductions, it is necessary first to break down and define the elements that make up these moldings.

In this article, I provide examples from the William and Mary, Queen Anne, Chippendale, and Federal periods. This visual glossary of elements and representative pieces will help you develop the vernacular and the know-how to identify and reproduce accurate crown moldings in your own workshop. Note that the periods and dates are approximations.

Also, styles overlap, and elements from more than one era often are present in a single piece of furniture. Each period produced certain styles of crown moldings, with makers within a period devising their own interpretations of the style. So it is impossible to make hard-and-fast definitions.

The following case pieces feature crown moldings that are representative of four distinct periods in different regions, including Philadelphia, Pa., and Boston, Mass., as well as Boston’s north shore.

William and Mary highboy—The one-piece cornice of this highboy is made up of a reverse thumb molding and fillet placed above an ogee, or cyma recta. Although it may appearthat these moldings were made with large molding planes, I believe that the cabinetmaker of this period would have used three separate planes. The coffin or smoothing plane would have been used to bevel the board, to create a chamfer, and to round off the tip of the thumb molding and the convex part of the ogee. For the fillets, a rebate would have been the plane of choice, and a hollow would have been used to cut the concave shape in the ogee.

I find this molding particularly striking in spite of its drawbacks. It lacks proportion between the waist and the cornice moldings. The waist is much larger in scale when compared with the cornice. Yet, overall, it has a commanding effect.

Queen Anne highboy—The swan-neck pediment is a defining element of the Queen Anne period. It starts with two fillets sandwiching a cyma recta. These elements are supported by a cove, followed by another fillet. The pediment then is completed with a quarter-round at its base.

In the mid-1700s, the swan-neck pediment was made up of one piece shaped almost exclusively with carving tools and scrapers. This represents a high level of skill because the craftsman had to saw a graceful S-shape while taking a profile from the side cornice molding and successfully carrying it along this dramatic swanneck

shape.

Chippendale chest-on-chest—Chippendale moldings transitioned from the Queen Anne period in a couple of unique ways. In most regions, the use of the swan neck continued into the Chippendale style; however, later examples reflect the classical architecture of the time.

The broken pediment illustrated on the facing page is a stunning representation of this evolution. The moldings on the pediment of this chest-on-chest are the same as those in the entablature—but with the addition of a cyma recta on the very top. The cornice sits upon a pulvinated (slightly curved) frieze. The architrave is a stacked series of fillets and cyma reversas. All of this is carried by a classical pilaster (a half column attached to the front of the case),which leads to the base molding and the pedestal that sits inside the waist molding.

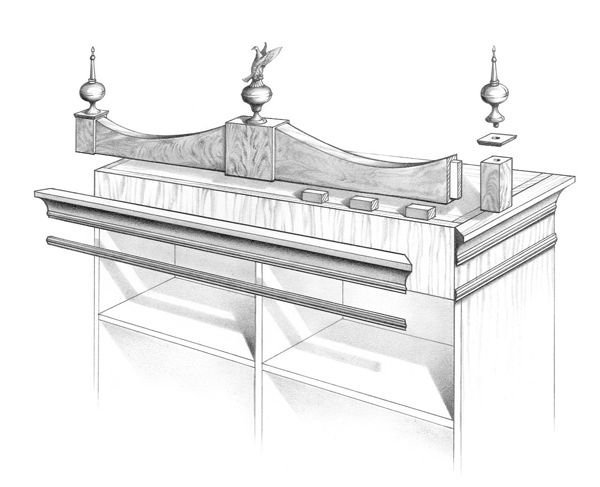

Federal desk with secretary—The Federal period really can consist of Hepplewhite and Sheraton furniture; both English styles influenced furniture design in the New Republic during this time.

Federal casework shows a toning down from the elaborate cornice designs found in earlier periods. The pediment of the piece shown in the PDF archive article above is made up of three pedestals and a connecting pediment board. The two end pedestals are capped with a solid-wood plinth cap with quarterround edges and brass finials. The central pedestal

has the same treatment, but perched upon it is the symbol of the Republic—the American Eagle. The use of crotch birch, veneered and inlaid, gives striking contrast. The veneered pediment lightens the overall appearance. The maker of this piece still employed a restrained entablature with the use of the fillet and cove on top of a bead with fillet. The frieze is crossbanded mahogany veneer (veneer applied vertically), and the architrave a mere astragal. This period relied heavily on the use of veneers and the contrasts they provide.

Philip C. Lowe runs The Furniture Institute in Beverly, Mass. For more information on classes, go to www.furnituremakingclasses.com.

From Fine Woodworking #166

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Bessey K-Body Parallel-Jaw Clamp

Blackwing Pencils

Festool DF 500 Q-Set Domino Joiner

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in