James Krenov Reflections

Reflections on the Risks of Pure Craft

One day in the early 1970s, while I was looking through a paperback on the crafts of modern Sweden, I came across a picture of a music stand made of lemonwood. Something about it, stirring in the slight tension of the curves of the legs, made me stop. The lines held something, a sense of memory. It was elusive, but in the form worked into the legs, I felt the craftsman had caught it; the wood seemed literally to be dreaming of the tree it used to be.

Incredible as that feeling was, the music stand wore it with unassuming grace. Nothing about it was forced. The execution of the piece was clearly exquisite, but without pushing itself at you. Work like that, I thought, isn’t born from the convulsions of ego alone. I looked for the name of the craftsman. The caption said, James Krenov. It was the first I had ever heard of him.

Times change. A few years have gone by, and now, a woodworker has to have been living under a rock not to have heard of Krenov. Since the publication of the first of his four books in 1976, countless craftsmen have read him. The voice he gives to an instinct to work wood in a certain way has become, by now, unmistakable. As a writer, he manages to touch the nerve that gives impulse to the longing for excellence, and many are the readers who respond in the way that a tuning fork, when struck, is made to hum. Some, though, find themselves torn-from trying to take what Krenov says to heart and still make some kind of living for themselves in wood. Others, frankly, are put off by his aesthetic prejudices, or find his moral tone too shrill. Regardless of your view, though, you know about him. The word, “Krenovian,” has come to be used to describe particular qualities of line, contour, detail-even of temperament. A buzzword, maybe, but the lexicon must have been missing something.

The forms that emerge in Krenov’s work have a quality of the inevitable, of having always been there, as though they just grew. It isn’t considered pragmatic, in the 1980s, to discuss wood in the language of druids. But in the face of work so closely fused to the nature of its material, I am made to believe in the transfiguration of objects. In its stillness, we continue to call a piece of Krenov’s a cabinet, and that’s what it is-a cabinet, flatly noted. But in its influence on feelings and for what it sets off in the mind, it takes on the magic of a talisman. A cabinet is only pieces of dismantled trees. Krenov makes me conscious that they were alive.

A critic, in my book, is little more than a dog in search of a hydrant. Lao-Tzu observes that, “He who speaks, does not know . . . He who knows, does not speak.” I believe him, but notice that he had to say it; I realize I risk being mistaken for a critic when I say that for my purposes, Krenov’s work is sometimes disturbingly small if looked at only as furniture. Because of its diminutive scale it sometimes has an air of something too much worried over, too nervous with the kind of fuss that makes more sense to me in the work of a miniaturist or a luthier. Because many of his pieces are only as large as they are, they are imperiled, in my mind, by their own delicacy.

On the other hand, a thing is what it is, and if you believe that things ask to be taken on their own terms, I wouldn’t argue that Krenov should be building shipping crates. There is a distinction made in Japanese aesthetics between things that are said to have the quality of being ripe and those that are said to have the quality of being raw. For the sake of comparison, George Nakashima’s work would be considered raw, and Krenov’s, ripe. Krenov, also, is aware of limits. Early in his career, he made a decision to concentrate on mall-scale work and he has done it at a pitch that metamorphoses a cabinet into a reliquary, or an ark, for the shelter of the idea of woodworking purely for itself.

Without asking that it be built any rougher, when I look at Krenov’s work it leaves me wondering what the actual use is, in our time, of furniture so extremely heightened in its workmanship. I have no interest in diminishing the drive that compels work such as Krenov’s, but I do have an interest in asking where that drive is going. What and who is the work made for? And what are the consequences, in a hyped-up economy, for those who try to survive by doing it professionally?

Sooner or later, a modern craftsman finds himself staring into the face of questions I like these. They have dogged me since I first started working through my ideas about furniture about 15 years ago. I don’t know if answers to them exist. Here, all I propose is to offer some interpretation of the questions. To establish an initial basis of understanding, I will start with a look at some observations on the nature of craft made earlier in this century by a thinker named Soetsu Yanagi. Later, I will try to align this understanding with my impressions of Krenov, from time spent in conversation with him and his students at his school in Fort Bragg, California, during visits to see them last year.

In the study of aesthetics in Japan, Soetsu Yanagi was a thinker comparable to John Ruskin, and later, William Morris, in England. His advocacy of the elemental in craft, and of craft’s need of a fundamental humility, was a strong influence in a revival of interest in the folk-crafts of Japan that began in about 1910, and still continues. In his book,The Unknown Craftsman, Yanagi concerns himself with the nature of the beautiful. He contends, with insistent eloquence, that the highest sublimity man ever achieves with his hands is almost invariably in work wrought in the humblest anonymity. Yanagi’s own most profound experiences of the beautiful were inspired by objects of craft made very much in the course of everyday life, without artistic calculation-things made without second thought, rapidly in great numbers, and cheap in cost . Many were tea and rice bowls, with glazes often crackled and uneven, and forms not flawless, but irregular. They were made, for the most part, by a faceless peasantry, people far too poor to be worried about personal aesthetic identities. By any measure of ours, they led lives of oppressive poverty, but they were lives rooted in cultures where there was nothing to threaten the place the artisan had in the scheme of things.

Necessity was the mother of Yanagi’s unknown craftsmen, and the crucible of “objects born, not made.” Work made under the enforced humility of poverty could not presume to dominate nature. Yanagi was convinced that the modern crafts, for all their higher sophistication, were distracted from the primal integrity which gives the peasant crafts their spiritual vitality. The strains of market competition put pressure on contemporary craftsmen to disdain nature in favor of artifice, which, as far as Yanagi was concerned, hurt their work. He didn’t go so far as to say that we should look around for ways to become impoverished, or start to make objects that look deliberately rustic or sloppy, in some hopeless affectation of the primitive making what David Pye delights in calling ” hairy cloth and gritty pots”), but Yanagi did say that he thought we were lost. The designer-crafts of our own time, ejected from the Garden, were not utterly barren of all grace, but to Yanagi , they bore the wound of separation. In contrast to the anonymous work of earlier times, he called ours the product of an Age of Names, or Age of Attribution-signature work.

The furniture most of us are making, as designer-craftsmen, usually doesn’t have too much to do with Yanagi’s idea of objects made for the simplest filling of need-unless it is the need to proclaim ourselves. But, says Yanagi, it is the object, the thing-in-itself, that speaks, not whoever happened to make it.

I think there is a vestige of Yanagi’s aesthetic and ethical values in James Krenov’s approach to furniture. Obviously, whether or not he literally engraves his initials into it, Krenov’s is signature work with a big S. The connection is not free of irony, but the values are there, in the preference in his work for quiet, or a little modesty, and in his relative unconcern for radically spectacular form. Krenov’s mastery, while it seeks to be there, still tries to deny itself. In that sense, his work asks that you look at it, and at the wood, instead of at him, and at least attempts to free itself of the modern’s consuming egotism.

The first time I was in Fort Bragg, my eye fell on one of the pieces Krenov has in his house. Very hesitantly, with exaggerated reverence, I began to approach it for closer look. Sensing that I was being conspicuously pious about it, Krenov said, “C’mon, go ahead, touch it…it doesn’t glow in the dark. ” He has yet to demand to be acknowledged as the Author of the King James Version. Most of his students, once past the first terrors of His judgement, just call him Jim.

If the desire for sublimity is what drives an artist to make art, while the impulse of a craftsman is to make a thing well, but to make it mostly for the satisfaction of utility, then what Krenov does is art more than it is craft. In Krenov’s shop, a piece grows hardly more quickly than the rings of trees. The main concern is not to bring a job in under the bid, but to express feelings, with the greatest possible emotional precision. Still, Krenov shrinks from being called an artist. I think it is because to him the word “artist” implies involvement with an avant-garde intent on setting the world on its head, and Krenov really isn’t interested in exploding all known conceptions of furniture. He is too much immersed in the processes of working wood. Seeing himself as a link in a furnituremaking tradition that didn’t start, and won’t end, with himself, Krenov is absorbed with doing work of a caliber that he feels the tradition demands of him, and encouraging his students to do the same. My impression is that he would just as soon let the question of Art take care of itself so he can get back to work at his bench.

As completely new as Krenov’s work is to most of us in North America, he didn’t just spring up, an unprecedented innovator, from out of nowhere. He has a lineage. There’s a long Northern European woodworking tradition, almost canonical in its purism. Earlier in this century, a leader in sustaining that tradition in Sweden was Carl Malmsten. Dedicated to reinvigorating the values he saw in the folk-arts of Sweden, Malmsten founded both a school and a cottage industry to promote Swedish craft. It was as a student at Malmsten’s school, from 1956 to 1958, that Krenov learned the classic techniques of cabinetmaking.

Malmsten’s designs are still in production, and in the Malmsten catalog Krenov’s genesis as a designer, and the seeds of what have come to be called Krenovian forms, can be seen in the outlines of Malmsten’s showcases, desks, and cabinets. “Originals?” asks Krenov, “what’s original? … if you look back far enough…” The point is that Krenov’s work expands on an inheritance, to which Krenov brings his extraordinary gifts for interpretation: a lyric sense of line, an eye for color and finely balanced proportions, and a genius for improvisation. (Malmsten always went strictly by the drawing-Krenov works mainly by the seat of his pants.)

The greatest number of Krenov’s pieces are cabinets; after that, smallish tables and stands; and then, cases and boxes, mostly for collections of rare objects. I asked Krenov why he never made dining tables, or beds, or (what I was most curious about) chairs-furniture types that have interested me most in my own work, because of their intimacy with the human condition: we have to eat, we have to sleep, and we have to sit. Krenov’s answer was honest enough, if just a shade evasive on the problems of working larger kinds of furniture with an approach as fastidious as his own. He said that he prefers to limit himself to what he does best, believing that there are craftsmen around who are better at doing the larger work, and that’s that. About chairs, he says, with discouraging conclusiveness: “The best chairs have already been done … by Hans Wegner, and by Esherick.” (I happen to like Krenov’s taste in chairs, but the fact that an excellent chair might already exist is no reason not to build one equally good. After all, there were also superb cabinets around, but Krenov still built his.)

In conversation, Krenov is reluctant to critique the work of his contemporaries. Underneath the surface, you know pretty well where he stands, but even his students find it difficult to pin him down for an aesthetic assessment of their own work. On matters of taste, strong feelings come up, and egos can get bruised. Krenov is no stranger to the problem. On the strength of convictions strongly stated in his books, he’s found his way into some nasty cockfights.

To know Krenov’s mind on questions of aesthetics, the place to look is in Krenov’s own work. There, what he thinks can be felt, by running a hand over the traces left by his tools on the coopered surface of a door, or by seeing the way the light races along a chamfer, or by touching the carving of a little pull. Imprinting the wood with a sense of the tool’s immediacy, his aesthetic confesses the process by which a thing gets made. As with his use of through-joinery, the directness of it reads as honesty, at least it does to those who see things in terms of the Arts and Crafts ethic.

The traces left by a plane give poignancy to the nakedness of surface, opening it to the sense of touch. Certain woods, such as pear, can be planed to a finish and left fresh, without sanding. The only direct means to the revelation of a surface-and the tool closest to Krenov’s heart-is the wooden plane. “Instruments,” he calls them, and it’s clear that he means, “… for the release of music.” When I first saw them, Krenov’s planes looked to me like the lumpy implements of Early Man, blunt shapes, the bodies roughly carved or left coarse from the bandsaw, scored or crosshatched for grip. The fact is, they are extremely sensitive and effective tools, no less sophisticated than the deceptively crude-looking planes the Japanese use. Other than all the planes and small knives he makes for himself, the rest of Krenov’s tools are surprisingly few, and very simple and ordinary. He’s worked out an economy of means and seems to have no great obsession with collecting them. Krenov’s appetite for wood-prime lumber-is another story. Last January, a group of us drove down to Palo Alto, 200 miles south of Fort Bragg, to select wood for Krenov’s students. A container had just arrived by ship from Stockholm, bought from a timber merchant Krenov used to deal with during his years in Sweden.

Observing the encounter of James Krenov with a load of lumber was worth the trip. As soon as he saw the lumber, he turned into a hummingbird. He began hovering in excitement among the tons of precariously stacked planks. I was afraid he’d break a wing. Paying no attention to his 65 years, Krenov whizzed and darted around. He threw himself into the work: unpiling and restacking planks weighing 200 pounds, seizing this, rejecting that, scrubbing at them with a block plane, all the while delivering a running commentary on each of their virtues and defects.

If Krenov had to choose a favorite wood, he says it would be pear, for its tranquility, its color, and its response to planes. The first lumber we sorted through was pear from Austria and France, steamed and unsteamed, 2 in. and 3 in. thick, sawn through-and-through. The paler, unsteamed pear is sometimes described in lumber lists as “pear, unsteamed, ivory.” I envy the student who works it. Next in the load was doussié, from Cameroon; then French walnut and cherry, and then elm, ash, maple, oak, hornbeam, beech and birch, from all over Europe . The lumber in the container was of mixed quality, some of it quite good, cut from close to the heart, but some was slash-cut (from out near the edges of trees), fast-waning and off in color, and most of that Krenov passed over.

The school Krenov directs in Fort Bragg is now in the fifth year of its existence. Its founding was the result of a tenacious effort by a group of the Mendocino region’s woodworkers to provide a permanent base for Krenov in this country. It isn’t a huge institution: 22 students are accepted into the program each year; a few remain for a second year. The program is an intensive nine-month course covering all the major points of Krenov’s technique, during which most of the students build several pieces of furniture and a number of planes.

The desire to learn from Krenov firsthand draws students from all over the world. In the class just concluding were two students from New Zealand, two from London, one from Norway, one from Hawaii (who chain-milled and brought native woods, including some very remarkable curly koa), two from Alaska (one a fur trapper, the other the builder of the trussed log bridge), plus students from around the rest of the United States. The diversity of their backgrounds and the lengths to which some of them have gone to get to the school says something for Krenov’s powers for arousing the will to pure workmanship.

The air is charged with Krenov, but the mood of the school is actually pretty loose. It isn’t a tyranny. The students are generally good humored and relaxed. A certain amount, not all, of student work bears a resemblance to Krenov’s, some of it very closely, which makes it tempting to criticize as merely the work of Krenovian clones, but I think this too conveniently misunderstands it. It’s plain to see that some of the students regard the imitation of a master as the price of becoming one oneself, but I also saw work being done that looks nothing at all like what one would associate with Krenov. As long as Krenov feels it is done with sensitivity and skill he doesn’t knock it, but it is clear, from the overall look of things, that Krenov isn’t running an art school consecrated to the worship of Design. As independent a spirit as Krenov is, he is still the exponent of an essentially conservative furniture tradition. He teaches a craft which has definite and settled criteria in his mind. There is room for experiment, but at heart, the school is committed to a classic way of cabinetmaking, not to the search for a profound originality, or to the idea of Design as an activity poised at the edge of the breaking wave of innovation.

Krenov’s compassion for the life of craft is evinced in all that he tries to give his students. Outsiders, dreamers, poets, monks, druids-his students find, briefly, the sanctuary a rare orchid finds in a greenhouse. I can’t help but wonder, though, about what happens when the year’s sweet interlude in Fort Bragg is at an end, and Krenov’s students hit the street.

It’s a raw question. I feel slightly wistful even asking it. Some of the students say they don’t seriously expect to make a living producing work as uncompromised as Krenov’s. They have the talent, but more than half of those I spoke with are reluctant to attach much professional ambition to it. They are there purely for the sake of studying under Krenov. More than a few, though, mean to survive as craftsmen on terms Krenov would recognize as his own. Given a few breaks, enough to preserve the obsession with integrity-who knows?-they might be able to patch together what Krenov likes to call “a modest living.” No less obsessed myself, I am no one to say otherwise, but I hate to linger too long on the odds.

When it comes to money, Krenov says that all he wants for his time is “what a plumber gets.” “Good luck,” I say to myself. If it’s any consolation to craftsmen miserable about not making enough money to get by, Krenov concedes that he hasn’t survived all these years himself by pluck alone-he’s had some help. It does nothing to diminish the beauty or the magnitude of Krenov’s achievement to celebrate the name of his wife, Britta Krenov. A woman of great warmth, very large patience, and the staying, power of a saint, Mrs. Krenov was for a long time the economic bulwark of Krenov’s passion. She is shy of being made a fuss over, but in reality, Britta Krenov is nearly as much the creator of Krenov’s contribution to woodworking as is Krenov himself. Without her, there might have been no Krenov, and personally at least, I’d be the poorer for it.

It is becoming increasingly difficult for a craftsman-Krenov and the rest of us-to know where he stands in contemporary life. In The Unknown Craftsman, Yanagi effectively pointed out that as a consequence of the Industrial Revolution the ancient basis of the crafts-necessity-has been eroded away. In the face of the remorseless onset of technology, the Arts and Crafts movement arose as a last great cry of protest against what was to be in fact an irrevocable change in the condition of man. Despite the profundity of the change, there remains in us a powerful compulsion to work with our hands. The emotion is so strong that in a few craftsmen it continues to translate into a drive to work wood for a living. The most viable form it takes is carpentry, still a going trade. What I contemplate here, however, is not the health of carpentry, but the fate of the classic trade of the cabinetmaker.

Interested in continuing to live through the workmanship of risk, the modern furnituremaker, in reaction to the crisis of an identity lost to industrialization, has had to cast around for something which will give a new legitimacy to the desire to build. Some of us have looked for it next door, in the art world. So, I think, begins the modern confusion of craft with art. The distinction between them has become so muddled that few people now are willing to say which is which. To the ruling taste, though, the crafts are the poor cousins of art. Established culture is inclined to attach much greater significance, not to mention money, to things called “art.” Wondering if the grass is maybe greener in the art world, furnituremakers start to strut their stuff as “art.”

In the utilitarian sense, art has never pretended it was useful. Furniture, supposedly, is. When it is posed as “art,” it puts something of a strain on its connection to its own origins in the principle of utility. Slipping his moorings, a craftsman gravitating into the art world comes under its pressures to produce things that are not artless but extraordinary. Only from looking for a leg to stand on, his work drifts into a situation infected with exactly the self-consciousness that worries Yanagi as the inevitable consequence of the move to signature work. In his insistence on the primacy of craft, Krenov has put up a notable resistance to the idea of himself as an “artist.” His work fights to escape falling prey to the excesses the art scenario seems to breed, but even he is not immune. None of us now building furniture, one lovingly considered piece at a time, really are.

As things stand now, the public has come to imagine woodworkers as a bunch of Gepettos, cheerfully at work on their Pinocchios. The public goes to galleries expecting to be awed by legendary feats of workmanship, or with an appetite for work of nothing less than staggering originality. A craftsman-particularly a younger craftsman-feels that he has to respond by showing work that makes a great display of virtuosity. There is a desperate novelty to the whole thing. Cursed with having to be clever, art-furniture has to jump through hoops, it can’t allow itself the rest of things simply at rest, not if it hopes to capture the fancy of prospective buyers. The situation seems to demand that, in the pursuit of an even more exquisite vulgarity, craftsmen turn themselves into performing dogs. One of the things that I admire about Krenov is his concern for the craftsman’s dignity, and his perception of the distortions that threaten to rob it of its composure.

Krenov has pointed out that the consummate craftsmen of our time are not necessarily professionals, It would be immodest to call myself “consummate,” but I think he’s right anyway, because as a professional I’m so chronically broke that I’m an amateur by default. Looking to make a buck or not, however, one thing is certain: as marginal artists, or as high-minded but low-tech holdouts, our work is no longer really answering to the broad base of social need-not in the way that the Windsor chair or the Shaker table once answered to it.

We are no longer constructing the relatively straightforward furniture of ordinary life. Modern hand-built furniture, whatever its aesthetic stripe, is built on a set of premises almost unrecognizable now to most consumers. The work of the fine craftsman is inherently and fundamentally disengaged from the values that drive the contemporary marketplace, It comes of the craftsman’s disgust with mediocrity-he recoils from it, understandably, The unpleasant side-effect of his withdrawal is that his own work starts to lack a certain relevance to the world as the world now is. Unwoven from the warp and weft of the prevailing reality, the craftsman, conscious that his skill is not especially needed, is left demoralized, emotionally and economically estranged from the energy that streams in everyday life. There is a bitter truth to Bob Dylan’s bottom line: “there’s no success like failure, and failure’s no success at all.”

Krenov can’t be blamed for any of this; he feels the crisis himself and tries to come to terms with it in his books. But the situation is paradoxical: work as fine as his inexorably raises the question of how it is to avoid its own extinct ion , While consumerism, driven by the engines of hype, is busy scaling new heights of delirium, the question of beauty is left to wander like some poor guy lost in the crowds at a trade show. From the point of view of survival, Krenov can’t give us an answer, because there isn’t one, unless its “just keep on truckin’.”

Krenov’s instinct is to work first from what moves in the currents of feeling and intuition. A few craftsmen will always be moved to approach wood and the work of furniture in the same way, inwardly, with absolute tenderness and rigor. As the work takes on the qualities of a closely meditated dance, the constraints of the equation of time with money are thrown aside. Krenov’s disclaimers of art notwithstanding, the craft practiced at this level is not simply a trade, it has entered the arena of quixotic risk, i.e. art, assuming for itself art’s conscious quest of the sublime.

In the understanding of Soetsu Yanagi, however, that very sublimity will more than likely elude the work of the signature craftsman because, in its self-absorption, the work is intolerant of imperatives that connect craft to life on Earth. If it is inessential to life, life will ignore it. Considered in that light, the furniture of the artist-craftsman is dangerously close to precious. Still, I keep making furniture by hand, but I suspect it’s because I was born to tilt the windmills: To my eyes, the radiance of the work of James Krenov is too compelling to dismiss with criticism of its economic unreality. It embodies an integrity, an equilibrium of thought and feeling, that graces far too little of the work of our time. Laying aside quibbles of art or craft, I find it hopelessly beautiful. Krenov has suffused the stuff of wood with a poetics, a mute poetics, a sense of word made flesh…and said things with it whose beauty no critic can explain away.

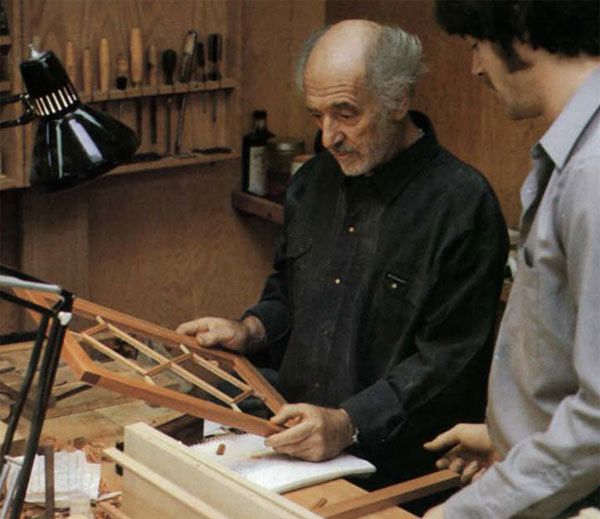

Photo: Nick Wilson

Originally published in Fine Woodworking #55

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Suizan Japanese Pull Saw

Circle Guide

Sketchup Class

Comments

I am lucky enough to have just completed the 2021 summer session at the Krenov School of Fine Woodworking. Happy to say the spirit of James Krenov is alive and well through the efforts of instructors Jim Budlong and Todd Sorenson, both former students of Krenov. Our instructors were very gracious in sharing their knowledge and consoling us when we made the inevitable mistakes. Getting acceptance into this class is difficult. The skills you will learn and your appreciation of the skills required to build gallery pieces make the effort worthwhile.

George Kinney

Fascinating essay to read, almost 40 years after it was written. This still seems to be true: " In The Unknown Craftsman, Yanagi effectively pointed out that as a consequence of the Industrial Revolution the ancient basis of the crafts-necessity-has been eroded away..... Unwoven from the warp and weft of the prevailing reality, the craftsman, conscious that his skill is not especially needed, is left demoralized, emotionally and economically estranged from the energy that streams in everyday life." I view the world of professional craft from the outside, but I suspect many craftspeople struggle with these same issues, as they try to find a place for their work in a world of Ikea and Instagram. So glad though, that the tradition represented here lives on.

A moving obituary of the author of this excellent essay here: https://www.startribune.com/glenn-gordon-furniture-craftsman-and-writer-dies-at-76/510489232/

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in