Synopsis: Finishing seems to create as many problems at the end of a job as bad preparation of wood creates at the start, writes Ian Kirby. In this article, he makes a few points about finishing: cleaning up, applying a finish, and assembly. He uses a sequence for each particular job, discusses the reasons to finish at all, and talks about choices of finish: varnish and lacquer, wax and shellac, and oil.

From Fine Woodworking #11

Compared to the paucity of attention given to the preparation stages of woodworking, a plethora of technical data is available about various wood finishes. Despite this, many otherwise fine pieces of work are spoiled at this final stage. Finishing problems seem to create as many problems at the end of a job as bad preparation of wood creates at the start.

Everybody seems to understand the need for extreme care and discipline when cutting joints and fitting pieces together. Yet when it comes to the finishing work, the time needed is usually underestimated. Then the urge to get the piece put together for the last time often overrides the need to assemble and finish in a considered sequence and under careful conditions. Ironically, an undignified rush to glue up before everything is absolutely ready inevitably requires substantially more time for finishing than would otherwise have been the case, and the result can only be less than acceptable.

This is not another article about wood finishes as such. It is an attempt to make a few points, which in my experience seem often to be forgotten at the finishing stage.

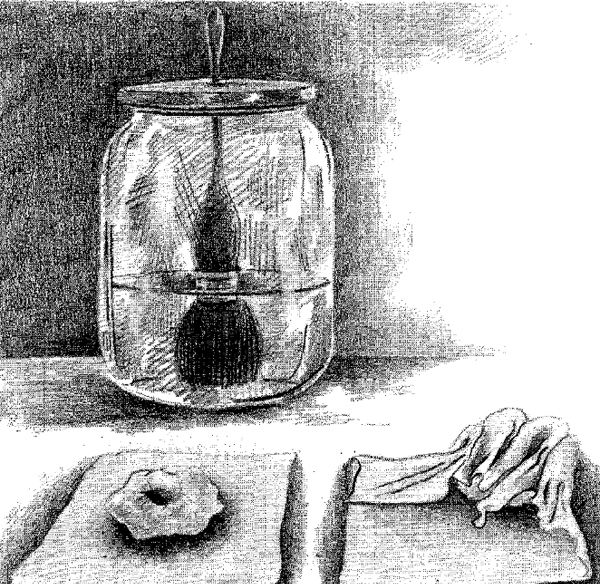

Cleaning up, applying a finish and assembly are all related parts of the finishing stage. The most common error is not to see them as such, especially where assembly is concerned. People glue together full or part assemblies and forget that it is far easier to clean up a piece of wood when it is separate from any other than to clean it up when it is glued into an assembly. Where two or more pieces come together at right angles to each other as in, say, a frame, it is virtually impossible to plane the inside surfaces or even to sand them properly without considerable frustration and sometimes taking the skin off the knuckles. Even when one is prepared to make this sacrifice, it remains impossible to reach right into the corners and a good crisp result simply cannot be achieved. It is also difficult to apply finish, at least by hand methods, to inside surfaces.

In general, it is best to prepare the surface for finishing with a minimum amount of sanding. The best finish comes from wood that is carefully smooth-planed, then sanded lightly (if at all) with 220-grit paper. This is particularly true when working ring-porous hardwoods, which may have considerable variation in density between earlywood and latewood. Excessive sanding cuts down the harder tissues in each growth ring, and depresses the soft tissues. As soon as the finish hits the wood, the compressed soft tissue springs back and the surface may become quite rough.

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Jorgensen 6 inch Bar Clamp Set, 4 Pack

Bessey K-Body Parallel-Jaw Clamp

Starrett 12-in. combination square

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in