Hello and Happy Holidays. I’m wondering how does one install shelves or drawer guides in a cabinet that’s constructed with frame and panel sides while accommodating wood movement? I know that with solid wood one can slot screw holes, or use sliding dovetails, and that with plywood wood movement is not an issue. But I don’t think I’ve seen people address this combination. (Or I wasn’t paying close enough attention) Thanks in advance,

Michael

Replies

Is there anybody out there? :)

I am sorry about the delay in reply but the holidays got in the way. Further complicating the problem it's not a subject you can cover in a few sentences. I am afraid I have written a tome, but it's hoped this can be a vade mecum for you and others. There is an axiom among cabinetmakers that it is hard to make money on a case piece. This is because there are a myriad of small hidden details in a good carcase that are never seen and seldom appreciated by the ultimate owner. These internal details, however, take a lot of time and make or break the piece. Nearly all plans and drawings assume that the builder knows how to execute these important internal details. If one does not know how to solve such details there are few texts or articles that treat this important aspect of cabinetmaking.

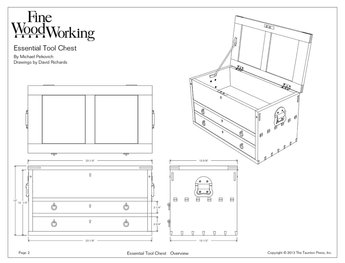

Internal framing must be done very carefully if drawers are to open and close properly. What is more this framing must be attached to the carcase itself in such a way as to allow for wood movement. Failure to do so will result in the framing destroying the carcase or vice versa. Further complicating the matter, dust panels are also included between drawers in the best work. In short the inside of most any case piece is full of stiles and rails (and possibly panels), put together with mortise and tenons, rabbets, grooves, stopped dados, housings, glue and mechanical fasteners.There are ample texts detailing their construction and I will not dwell on this subject other than to say that it is only one half of the problem. Drawers have to be supported and this is the function of what is commonly called drawer slides. Anything that supports a drawer can properly be called a drawer slide. Carcase construction can be divided into solid wood and frame and panel. Each type of construction requires separate solutions to the wood movement problems. We will look at the latter.Stiles: Called bearers by the British, stiles are narrow wood strips that run from the front to the back of the carcase and support the bottom and usually the top of the drawers. The inside edge of these rails are grooved when a dust panel is included. I prefer the British term and will use "barer" throughout the rest of this treatise.

Rails: The rails run across the carcase for purposes of strengthening and attaching the internal frame work and trapping a dust panel if employed. The inside edge of these rails are grooved when a dust panel is included.Guides: Guides are wood strips (or in some cases the carcase itself) that control the lateral movement of the drawer. The guides are most commonly glued and/or nailed at right angles to the bearers.

Kicker: Wood strips glued and/or nailed to the carcase, or the bottom of the bearer to prevent the drawer from tipping too far downward when open.Stop: In flush face construction the drawer stops prevent the drawer from sliding back inside the carcase, so that the front of the drawer is flush with the face when closed. Stops are, of course, unnecessary with lip face, or overlay face construction for the drawer itself provides the stop when it rests against the cabinet face in the closed position.Frame panel construction is typical of chest of drawers and very large case pieces such as wardrobes. Here panels are held by stiles and rails which also form the structure of the carcase. Often square legs become the stiles. This variation is often referred to as post and rail, or post and panel construction. For clarity I will use the term post for stile, because this clearly refers to the carcase and not the drawer slides. Wood movement in post and frame construction is not as great a problem as with solid wood carcasses. The posts and frames of the carcase now mimic the wood movement of the drawer slide frames. The solution is to support the drawer slide frames (often called web frames) in housings (or notches if you will) cut in the posts.In the very best work of the past web frames are held together by mortise and tenons and trapped in housings cut in the front and rear posts. In this highest quality work the web frame rails are made 1/2" longer than the web frame size, and trimmed to form a leg on the end ( 1/4" x 1/4" by the thickness of the web frame which is usually 3/4"). This leg is housed in the front post by cutting a deeper mortise at the front of each notch to match the leg protruding on each end of the front web frame rail. Today most workers eliminate these protrusions and just house the four corners of the web frame in notches cut in the posts. It is important that the housings allow for wood movement in the drawer slide frame. Correctly done the frame may be move a bit side to side and front to back during dry assembly. It should not, however, move up or down. During final assembly the front web frame rail is glued to the face frame rail (unless it is housed as per my drawing). In good case work either the drawer or the guides should be tapered a bit. Generally, the drawer needs to be about 1/16" narrower at the back (or the guides about 1/16" wider) than at the front. Since the guides are glued in place it is a simple matter to cut a couple of sticks from scrap, one the opening of the face frame and the other 1/16" longer. These can be used when setting the guides to give the desired taper to the slides. Wire nails are very handy to attach the guides while the glue dries. I have always found this option to be cumbersome, and where there are several drawers across the taper ends up all to one side unless keystone shaped intermediate guides are cut. All this entails a lot of hassle.I favor making the guides square and tapering the drawer. With hand dovetailing this happens naturally for the half blind at the front of the drawer is cut to the exact thickness of the side stock and the through dovetail at the back is cut about 1/32" deeper than the thickness of the stock. This naturally puts about 1/16" taper in the drawer. Even with better router jigs such as the Leigh or the Omni this feature of hand cutting can be mimicked. With other forms of joinery, such as lock miter joints, the back can merely be cut 1/16" narrower than the front. The result is a drawer that opens easily but can be closed from a half open position by placing one finger at the extreme edge and pushing. To me this is the acid test that every drawer should pass. Try a bit of paraffin on all contacting surfaces before conducting this little test, however. It is always good to load the deck in your favor. In case work we need all the help we can get.Attached are some photos of a Shaker Sewing Cabinet I use as and advanced course to teach just this subject, Internal Framing. They should edify all of the above a bit. If you have further questions please ask.Wishing you a Happy New Year

Ernie Conover

Edited 1/5/2007 10:06 am ET by ErnieConover

Wow. That was way more of an answer than I could have hoped for. Thank you very much. I'll have to study this a bit, but I believe I followed you. Thanks again, and Happy New Year.

Michael

Your are entirely welcome. Hope you can get on with the project now. With best regards,

Ernie Conover

This forum post is now archived. Commenting has been disabled