9 Reasons to Own a Shoulder Plane

Fine-tune your joinery with these tips and techniques.

With its narrow profile, precisely milled sole, and blade that cuts fully into corners, the shoulder plane is much more than a specialty tool. In fact, contributing editor Chris Gochnour uses this narrow-bodied handplane almost every day. Here, he details nine different applications on a single project where the shoulder plane was the best tool for the job: trimming tenon cheeks to fit; refining tenon shoulders; tuning dadoes and grooves; cutting rabbets; tweaking rabbet joints; adjusting tongue-and-groove joints; removing machine joints; softening sharp edges; and trimming mitered molding.

It’s easy to dismiss the shoulder plane as a “specialty” plane, another way of saying it has limited use in most shops. But that has not been my experience. I use this tool almost every day in my furniture-making shop. When I teach woodworking and show students what the shoulder plane can do, it quickly becomes the most borrowed tool from my tool chest.

Early in its history, the shoulder plane was used most often to plane the shoulders of hand-cut tenons, hence its name. The blade is bedded at a low angle, with the bevel facing up, making it well-suited for planing end grain. It can be used one- or two-handed.

What really sets the shoulder plane apart from other handplanes is its narrow body profile, with the sole precisely milled square to its side and a blade that spans ever-so-slightly beyond the full width of the sole (see drawings, facing page). That means the blade is sure to cut fully into a corner without producing an unsightly cut line. Granted, you can use a chisel to get into a corner, but a shoulder plane does it faster with more control. Because the side of the plane and the sole are square to each other, each face of the corner remains square. Also, compared to a chisel, the plane makes it easier to keep the surfaces perfectly flat.

I reach for my shoulder plane all the time. Indeed, when making a wall cabinet recently, I used the plane in nine different places. For many of these tasks, the shoulder plane simply is the best tool for the job. The following pages illustrate some of the more common ways I put a shoulder plane work. No doubt there are other applications as well.

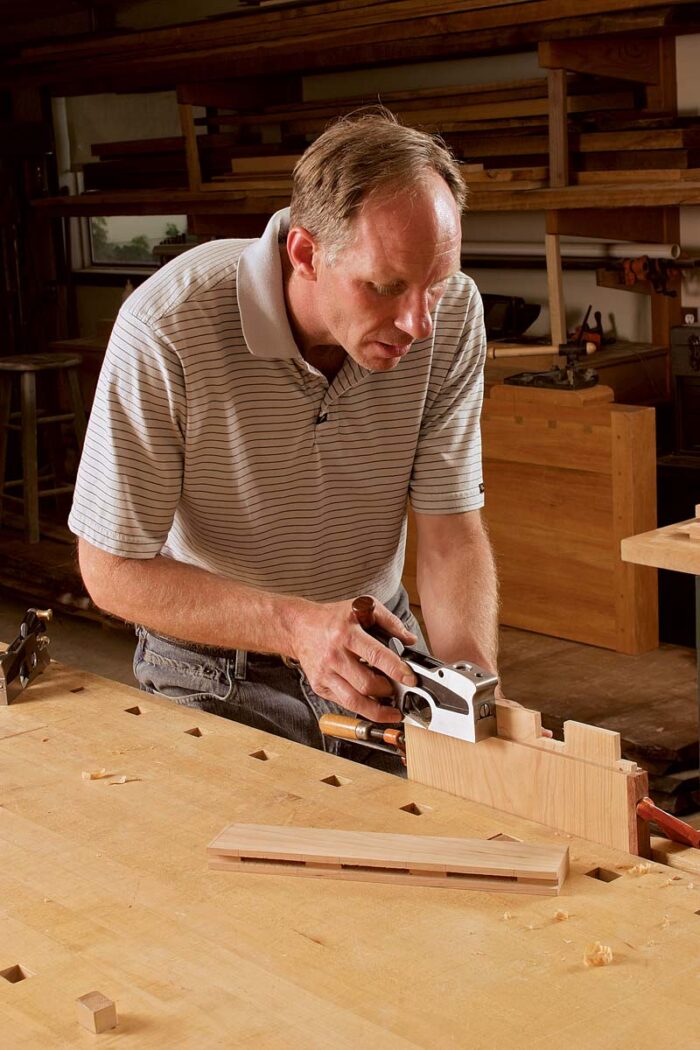

1. Trim tenon cheeks to fit

Perhaps the task where I use a shoulder plane the most is fine-tuning the fit of tenons to their respective mortises. I use machinery to cut the tenons. But I don’t aim for a perfect fit from the machines, mainly because there are enough slight variables in the process to make perfection hit or miss. Instead, I use the machines to produce a very tight fit. Then, when it’s time to dry-assemble the parts, I use the shoulder plane to shave each tenon cheek. This gives me complete control, and I end up with a perfect fit every time.

Before starting, set the plane for a very light cut. Check to make sure the blade is parallel with the sole of the plane. Plane across the grain, taking light passes. If the tenon is longer than the plane is wide, use slightly overlapping passes, starting at the shoulder and working toward the tenon end.

Be sure to plane the same amount from both cheeks. If you don’t, the position of the tenon relative to the face surfaces of the workpiece will change slightly, and the face surfaces of the mating parts won’t be perfectly flush when assembled.

There’s another advantage to starting with a tight fit. If, during dry-assembly, I discover any misalignment of the face surfaces of the mating parts, I can make a correction. This is done by identifying where the joint is misaligned and planing one cheek of the tenon until the misalignment is corrected.

While I’m at it, I use the plane to chamfer the tenon end. This helps reduce the amount of glue that gets scraped to the bottom of the mortise during glue-up.

|

|

|

Trim tenon cheeks. No matter if the workpiece is narrow or wide, a few light passes with the shoulder plane on each tenon cheek will transform a tight-fitting joint into one that fits perfectly |

2. Refine tenon shoulders

Traditionally, tenon shoulders were cut with a backsaw, then cleaned up with a shoulder plane. While today’s woodworker probably makes shoulder cuts on a tablesaw, there are occasions where misalignment creeps in. With its low-angle, full-width blade, sole squared to its sides, and solid construction, the shoulder plane excels at working those tough end-grain fibers.

When working shoulders, set the plane for a very light cut and make multiple passes. If planing a narrow shoulder like that of a cabinet door, use a bench hook to support the stock. Lay the board flat on the bench hook and align the shoulder flush with the end of the bench hook’s planing stop. This supports the edge of the shoulder and helps prevent splintering. To prevent splintering when working on wide shoulders, clamp the workpiece in a vise with the tenon facing up. Make your first planing cuts from the end of the shoulder to the middle. Then do the same from the opposite end of the shoulder. Work carefully so that the shoulder line remains straight.

|

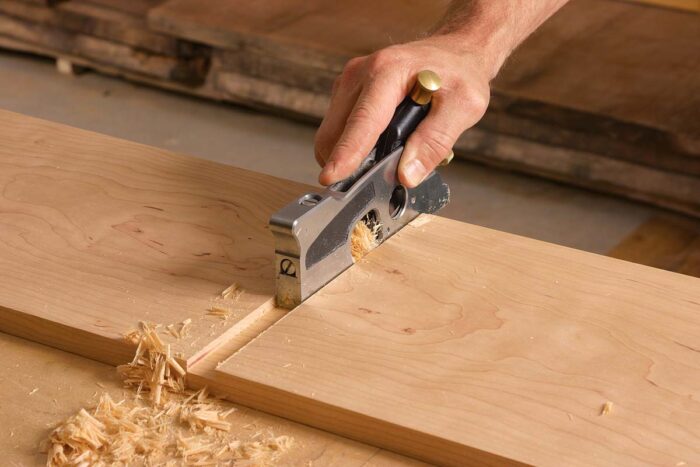

3. Tune dadoes and grooves

Every now and again, a dado or groove needs to be cut a little deeper. If the joint is wide enough to

accept a shoulder plane, I use one to do the job. It’s generally faster and easier than resetting the

machinery that made the cut initially.

At each end of the dado or groove, use a marking gauge to define the new depth. Adjust the shoulder plane’s mouth opening and blade depth for a medium cut so that the work progresses quickly.

To help avoid tearout, start by planing from one edge of the workpiece toward the middle of the piece. You need only plane for a few inches. Then do the same from the other end. Finally, plane the area between the end cuts.

Sometimes I cut a dado entirely with hand tools. To do this, use a backsaw to cut the dado sides to the desired width and depth. The material that remains is removed mostly with a paring chisel working across the grain. Then, the shoulder plane finishes the job in the manner described above.

|

|

|

Deepen a dado or groove. A dado or groove that’s too shallow can be deepened by establishing the new depth on each end with a marking gauge (above left). Then the shoulder plane is used to cut to the marked lines (above right). |

4. Cut rabbets

A shoulder plane can cut small rabbets. First, define the base and depth lines with a marking gauge. Then, to create a fence, clamp a straightedge board to the workpiece, making sure it is aligned with the baseline.

Open the mouth of the plane to about 1⁄32 in. to accommodate heavier shavings, and then advance the blade for a medium cut. Hold the plane in both hands with its side firmly against the fence. Make multiple passes as needed. When you reach the depth lines, the rabbet is complete.

|

|

|

Cut a rabbet. First use a marking gauge to mark the rabbet width and depth (above left). After that, clamp a wood straightedge to the workpiece and start cutting (above right). |

5. Tweak rabbet joints

Rabbets are mainstays in woodworking joinery and often will benefit from a tweak with a shoulder plane. I periodically use the tool to correct a misshapen opening for a cabinet back, to improve the fit of a rabbeted case joint, or to size the rabbet of a recessed door panel to just the right fit in a door frame.

Many shoulder planes have a unique feature—they convert to a chisel plane in no time. When a corner meets a corner, like when two rabbets meet at right angles, a chisel plane is the perfect tool for getting into that corner.

|

|

|

Fine-tune a rabbet. A rabbet that’s a little too fat can be thinned simply by making a few passes with the plane (above left). Rabbeted parts that are slightly misaligned when assembled can be quickly realigned by converting the shoulder plane into a chisel plane (above right). |

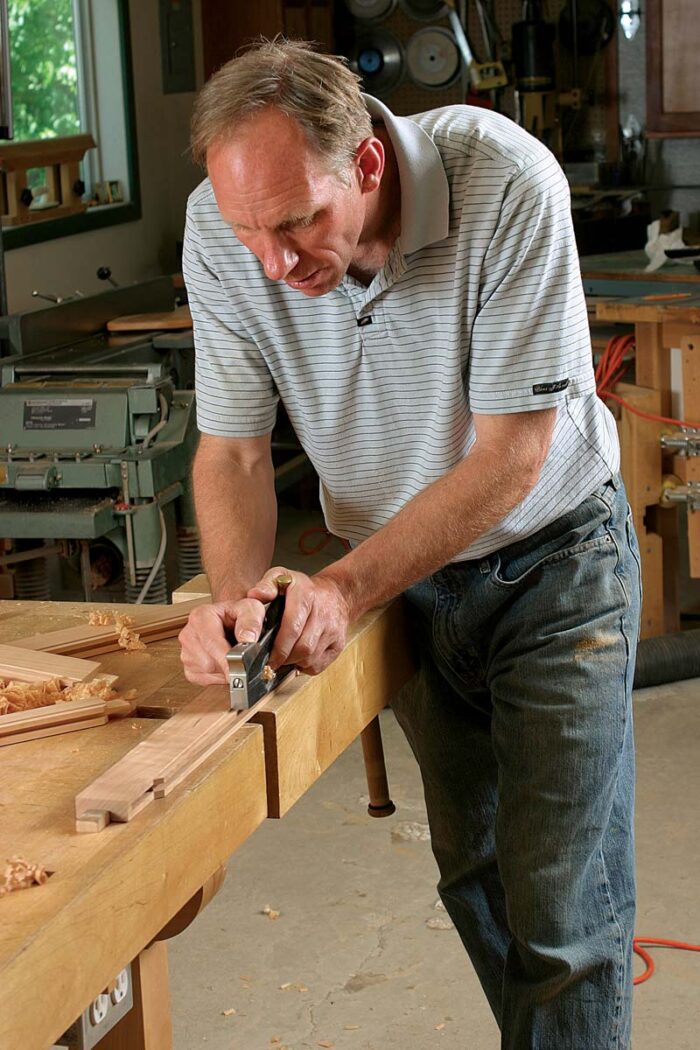

6. Adjust tongue-and-groove joints

I like the look of tongue-and-groove boards on cabinet backs. I try to fit this joint tight off my machines so that the alignment of the boards is just right. Every now and again, though, a joint is a bit tight and requires the tongue to be slightly thinned. I’ll finish it in no time with a few passes of the shoulder plane.

Hold a small board in one hand and plane with the other. On a larger board, plane with both hands, securing the board to the workbench with bench dogs and the tail vise.

Take a shaving or two off each side of the tongue and check the fit. Continue until the fit is perfect.

|

Tweak a tongue. A tongue-and-groove joint is a chore to assemble when the tongue is too tight. A few swipes on each side of the tongue solves the problem in short order. |

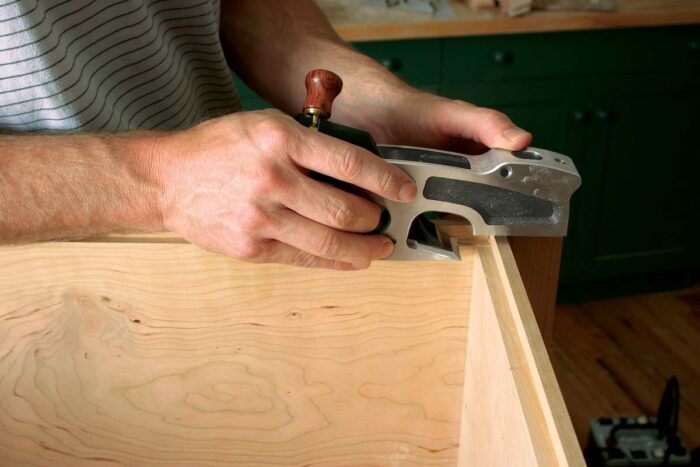

7. Remove machine marks

On flat surfaces, milling marks are easy to clean up with handplanes, scrapers, or sanders. But a shoulder plane is the best tool for cleaning up inside corners.

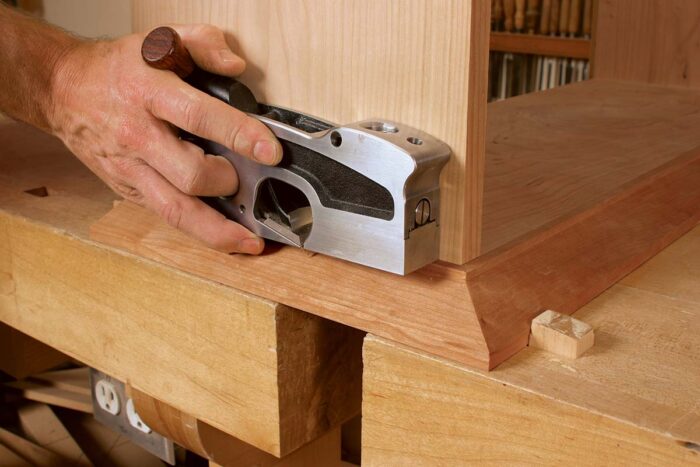

On the top and base molding of this cabinet (right), I can plane right up to the raised lip that’s machined along the entire length. However, I need to work carefully because I don’t want to alter the depth from one piece of molding to the next. I handle this by setting the plane for a very light cut and letting the machine marks serve as a reference to show where and how much material to remove.

On the shallow rabbet that decorates the inside edge of the cabinet door (facing page), I need to remove the router-bit marks before assembly. The shoulder plane is perfectly suited for the task.

A spare plane blade, sharpened to a steeper angle (35° to 40°), can come in handy for long-grain areas with tricky grain. The steeper cutting angle reduces the prospect of unsightly tearout.

|

8. Soften sharp edges

I use a shoulder plane to soften sharp edges that are inaccessible with other planes. For example, on a beadboard back, it’s easy to soften the sharp edge on the milled bead by reaching in with the edge of a shoulder plane. Because the blade isn’t sharpened on its side edge, the plane won’t mar the details that are adjacent to the edge being worked.

To soften or round the edge, set the blade for a light cut and begin with the plane tipped on its edge at about a 50° angle, with the corner of the blade reaching into the bead. Make a series of passes, rolling the plane more upright with each successive pass.

|

Go places other planes can’t. The sharp edge adjacent to the beaded edge of the cabinet backboard is easy to soften with a shoulder plane. |

9. Trim mitered molding

The crisp alignment of mitered moldings is a hallmark of fine craftsmanship. Try as I might to get things just right, there are occasions where after the glue is set, slight adjustments must be made to the fit of the molding. These are especially problematic where the molding meets the front or side of a case.

A shoulder plane can be used here as you might a chisel, but with a sole to add control. With a shoulder plane you can carve, shape, and realign moldings for a clean, crisp look.

|

Plane moldings flush. The top edges of the front and side base moldings were slightly misaligned. Gochnour uses a shoulder plane to get the parts flush. |

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in