The Mortise and Tenon Joint

Best results come directly from chisel and saw

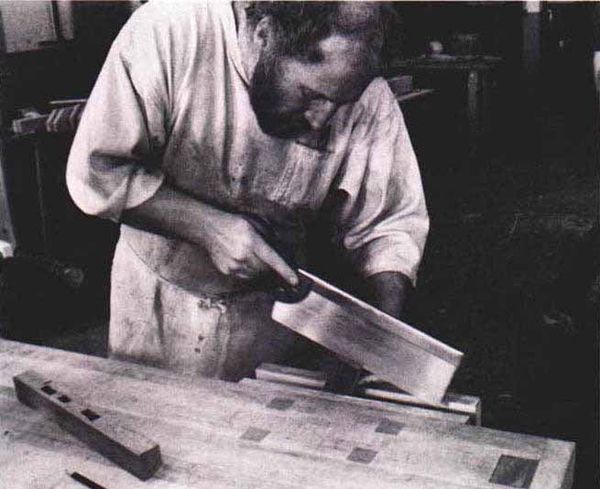

Synopsis: Ian J. Kirby says the mortise-and-tenon joint is fundamental to woodworking. In this article, he focuses on the basics of designing mortise-and-tenon joints to fit their purpose in a structure and on how to make a single joint with hand tools. He outlines common mistakes made in designing, shares general rules to make the joints, and then discusses the tools needed for this type of job. He explains how to set the mortise gauge, knife the shoulder lines, chop the mortise, saw the tenon, and check the accuracy before assembling the joint. Photos and drawings illustrate every aspect of the joint.

From Fine Woodworking #15

The mortise and tenon joint is used to bring two pieces of wood together, usually at a right angle, as in frames for carcases and doors, table legs and aprons, chair legs and rails. It is fundamental to woodworking and is made in innumerable variations, either by hand or machine. This discussion will focus on the basics of designing mortise and tenon joints to fit their purpose in a structure, and on making a single joint with hand tools. When there are only a few to do, a skilled workman will hand-cut them in the time it would take to set up machines.

A mortise and tenon joint gets its strength from the mechanical bond of letting one piece of wood into another, and from the adhesive applied to closely fitting long-grain surfaces. The craftsman must design the relative proportions of the mortise and tenon in order to best resist the forces the joint will encounter in service, to balance the wood tissue between the mortise and the tenon, and to maximize the longgrain gluing surfaces. Then he must make the parts accurately and cleanly, in order to achieve a close interface and thus a strong glue line.

A common mistake is to search in books for formulae and schematic diagrams of universal application. Instead, one should analyze the function of the joint in the structure one wants to make, and the loads it will have to bear. Does it have to resist downward pressure, or tensile load, or bending and twisting forces, or as is frequently the case, a combination of a number of forces? Knowing exactly what performance one wants from the joined pieces should be the first step in designing the joint.

The general rule is that there must be enough wood on the tenon, both in length and in section, to withstand the load it will have to bear. If the load is exclusively downward the tenon should be thick, but there is no need to have thick mortise cheeks. On the other hand, if there will be twisting forces, both the mortise cheeks and the tenon must be thick enough to withstand them. If the force is an outward pull or a pivoting, the tenon should be long enough to provide ample gluing area, or long enough to pass right through the mortise so it can be wedged on the other side.

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Marking knife: Hock Double-Bevel Violin Knife, 3/4 in.

Veritas Precision Square

Suizan Japanese Pull Saw

Comments

Started woodworking in the mid eighties. I was fortunate enough to live in Atlanta near highland hardware. I bought Ian Kirby's books. He had a BIG influence on me.

Cheers!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in